Feature

Article

Sponsored Content

Empowering Advanced Practice Providers to Adopt Routine Screening for Tardive Dyskinesia

This article was developed and sponsored in collaboration with Neurocrine Biosciences, Inc. Amy LaCouture, RN, BSN, PMHNP-BC and Linda Trinh, DNP, MPH, FNP-C, PMHNP-BC have been compensated by Neurocrine Biosciences, Inc. to author this article and share their perspectives.

Tardive dyskinesia (TD) is an involuntary movement disorder associated with the use of dopamine receptor-blocking agents (DRBAs) that can range in severity and presentation and can impact social, emotional and functional components of daily life. There are treatments that can effectively manage TD, but first it needs to be recognized and accurately diagnosed.

Tardive dyskinesia (TD), a movement disorder characterized by uncontrollable, abnormal and repetitive movements of the face, torso, limbs and fingers, or toes, can add a significant burden for patients already managing a mental illness.1 Proactive recognition of the disorder can have a positive impact for patients. Asking the right questions and making observations during routine interactions can aid in identifying the full impact of TD, including how patients may compensate for the disorder, self-awareness of the uncontrollable movements and impact on daily life. All advanced practice providers, including family and primary care providers, can help improve the recognition, diagnosis and management of patients with TD by making screening a part of their clinical routine for all patients on dopamine receptor-blocking agents (DRBAs), such as antipsychotics and antiemetics.

Understanding TD and Its Impact

TD is a persistent, involuntary movement disorder associated with the use of DRBAs, such as antipsychotics or antiemetics. It is estimated to affect at least 800,000 people in the United States.* According to a 2017 meta-analysis of 41 studies, between 7.2% and 30% of patients taking antipsychotics had TD, with the degree of prevalence dependent on exposure to first- or second-generation antipsychotic use.2 While anyone with exposure to antipsychotics can develop TD,2 increased risk factors include being age 50 years or older,3 history of substance use disorder,4 being postmenopausal,5 diagnosis of mood disorder,6 cumulative exposure to and potency of antipsychotics,4,7 treatment with anticholinergics4 and history of acute drug-induced movement disorder (DIMD).4

TD is often persistent and irreversible and can range in severity and presentation.8-11 The impact can be multifaceted (eg, social, emotional, psychological and functional). Therefore, impact should not be determined based solely on movement severity.12 Identifying and managing TD while concurrently maintaining control of the underlying psychiatric disorder is important given TD can add to the overall burden of illness.

Challenging the "Wait-and-See" Approach

Proactive recognition and treatment of TD can make a positive impact in the lives of many patients with psychotic and mood disorders. It is important to initiate conversations with patients to uncover the potential presence and burden of TD.

Insights from the RE-KINECT® study, the largest real-world, observational multicenter study of antipsychotic-treated patients with possible TD, suggest clinician-rated severity of TD may not always correlate with patient perceptions on the impact of the condition on their daily lives.13 The data reinforce the importance of not only assessing the possible presence and severity of TD, but also assessing patient awareness of their own abnormal movements and the impact of these symptoms on their overall wellness and ability to function to determine optimal management strategies.

When assessing the signs of TD, consider asking how it may be affecting patients’ everyday lives. For example:

- When did you first notice the movements? What did you think about them?

- Do these movements make you feel nervous or embarrassed around others?

- How has your social life changed because of your movements?

- Do these movements make you feel anxious about going out in public?

- Have other people noticed your movements? If so, what did they say?

- How has your work or career changed because of your movements?

- How has your daily routine changed because of your movements?

- Are there activities that you avoid or that you’re unable to do because of your movements?

Treatments approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for TD have been available since 2017, making timely recognition and diagnosis critical. Vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 (VMAT2) inhibitors are recommended as first-line treatment for patients with moderate-to-severe TD by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) guidelines and may also be considered in patients with mild TD based on factors such as patient preference, associated impairment or effect on psychosocial functioning.14

Taking Steps to Increase Routine TD Assessment

In Person

APA guidelines recommend routine screening for TD before starting or changing DRBA treatment, monitoring for signs of TD at each visit and conducting a structured TD assessment every 6 to 12 months, depending on risk, and if new or worsening movements are detected at any visit.14 As providers who are particularly attuned to establishing and maintaining relationships with patients and collaborating with the broader healthcare team, advanced practice practitioners can take a leading, proactive role in increasing routine screening practices.

Screening can be done in any setting simply by observing the patient unobtrusively in their own environment for community practice or the waiting area as they make their way to the exam room. Once in the exam room, ask the patient to remove their shoes and socks to see any foot or toe movements, and observe the tongue at rest to identify changes in movement. To help reveal facial and leg movements, try physical or cognitive activation maneuvers or distraction techniques, such as having the patient tap each finger to their thumb rapidly or recite the names of the months. Finally, observe movements of the trunk, legs and mouth during interactions. In addition to these observations, consider the following two assessments that can be integrated into clinical encounters:

- The Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS), a 12-item observer-rated scale, serves as a subjective assessment to identify movement and is the standard structured instrument for assessing TD severity.15

- The MIND-TD questionnaire can help with semi-structured TD assessments at each visit and is intended to help guide an exam from initial screening. Consisting of two parts, it is designed to facilitate a dialogue about abnormal movements with patients at risk of TD and help guide next steps if TD is suspected.16

It is important to note that neither the AIMS nor the MIND-TD questionnaire serve as a diagnostic tool. Diagnosis of TD should be based on each patient’s medical history, symptoms and the clinicians’ best judgement.

Via Telehealth

When an in-person visit is not possible, TD can be assessed via telehealth with the help of a care partner, as needed. Tips for a successful visit include:

- Asking the patient to use a smartphone, tablet or laptop that can be easily maneuvered and positioned, if possible, as this may help with seeing various body regions.

- Asking the patient to use a well-lit, uncluttered room with space to take several steps, as well as a firm chair without armrests.

- Requesting the involvement of a care partner who can help position the camera, assist with technology or facilitate questions.

Many elements of the AIMS can also be addressed via video:

- Use a laptop or tablet instead of a phone screen to clearly see the patient’s arms, legs and feet.

- Observe various body regions, such as eyes, lips, face, hands and fingers, shoulders and tongue, both with and without activation.

- Be prepared to model actions for the patient, especially for activation maneuvers.

- Consider performing the maneuver at the same time as the patient to help them feel more comfortable.

- Ensure the camera can be tilted downward to examine the patient’s feet and toes.

Differential Diagnosis of TD

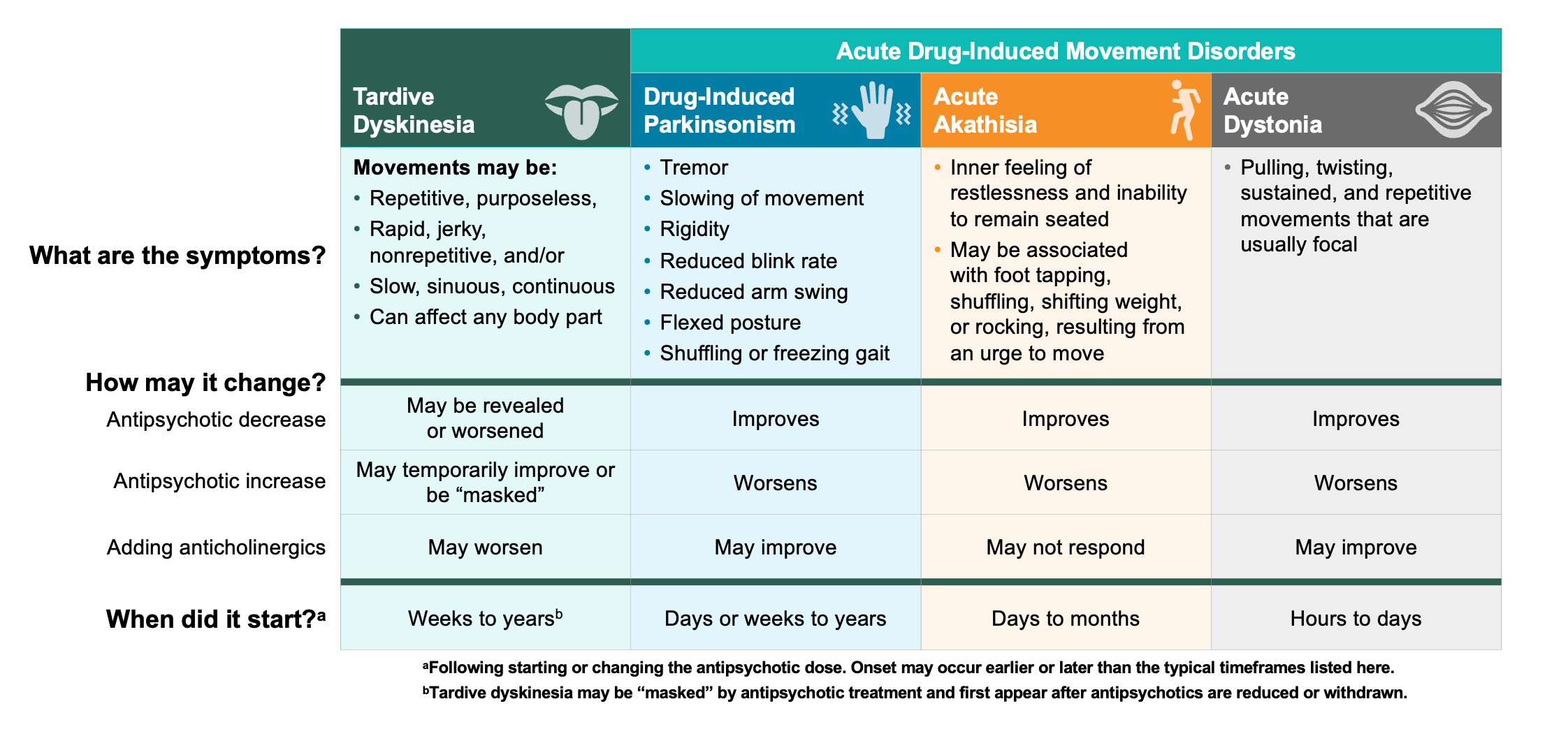

TD must be differentiated from other DIMDs because recommended management strategies differ. Extrapyramidal symptoms has been used as an umbrella term for various DIMDs; however, TD is a clinically distinct DIMD.8,17 Importantly, while anticholinergics may be used for some DIMDs, treatment with those medicines (eg, benztropine) is not recommended for TD, as it can worsen symptoms.14,18 The key to a differential diagnosis is knowing what the characteristic movements of different DIMDs look like, though other aspects of the patient history, such as any recent medication changes, can also provide clues (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Differential Diagnosis of TD8,10,14,19

Proactive Management of TD

The involuntary and uncontrollable movements of TD not only impact patients physically, but also emotionally and socially.1 When assessing signs of the condition, ask about how TD is affecting everyday life. Timely TD recognition and comprehensive understanding of the full impact can help facilitate early treatment intervention and may help mitigate the disruptive symptoms that some patients experience. VMAT2 inhibitors are the preferred first-line treatment for TD.14,20,21

Approved by the FDA in 2017, INGREZZA® (valbenazine) capsules is a highly effective VMAT2 inhibitor for the treatment of adults with TD and the treatment of chorea associated with Huntington's disease. Uniquely selective, INGREZZA results in slow and stable production of one primary metabolite, (+)-α-HTBZ, which has a high affinity for VMAT2 and negligible affinity for off-target receptors, including dopamine, serotonin and adrenergic receptors.22,23†

INGREZZA offers a therapeutic dose from Day 1 that can be adjusted by the clinician based on response and tolerability. INGREZZA does not require complex titration, and patients can remain on their stable psychiatric treatment regimen.24 Additionally, INGREZZA is the only VMAT2 inhibitor available in a sprinkle formulation. The sprinkle formulation, called INGREZZA® SPRINKLE (valbenazine), is an option for patients who experience dysphagia or difficulty swallowing or prefer not to swallow whole pills. INGREZZA and INGREZZA SPRINKLE dosages approved for use are 40 mg, 60 mg and 80 mg capsules.

Select Important Safety Information

Depression and Suicidality in Patients with Huntington’s Disease: VMAT2 inhibitors, including INGREZZA and INGREZZA SPRINKLE, can increase the risk of depression and suicidal thoughts and behavior (suicidality) in patients with Huntington’s disease. Balance the risks of depression and suicidality with the clinical need for treatment of chorea. Closely monitor patients for the emergence or worsening of depression, suicidal ideation, or unusual changes in behavior. Inform patients, their caregivers, and families of the risk of depression and suicidal ideation and behavior and instruct them to report behaviors of concern promptly to the treating physician. Exercise caution when treating patients with a history of depression or prior suicide attempts or ideation, which are increased in frequency in patients with Huntington’s disease.

Please see additional Important Safety Information, including Boxed Warning, below.

Efficacy and Safety of INGREZZA in Adults With TD

The efficacy and safety of INGREZZA was evaluated in the Phase 3 KINECT®-3 clinical trial. Participants in the clinical trial experienced approximately a 30% reduction in TD severity with INGREZZA 80 mg at 6 weeks.‡ A 3.1-point greater reduction for INGREZZA 80 mg vs placebo was observed in AIMS scores at Week 6, with results seen as early as Week 2 (Figure 2).24,25

Figure 2: Least Squares Mean Change From Baseline in AIMS Dyskinesia Total Score Through 6 Weeks (Intention-to-Treat Population)24–26

60-mg data based on modeling and simulation. The LS mean is adjusted for baseline AIMS score and disease category and is shown for consistency with 40-mg and 80-mg observed values from the KINECT-3 study.

aP ≤ .001 dose that was statistically significantly different from placebo to control for multiple comparisons.

Mean baseline AIMS score (standard deviation): placebo: 9.9 (4.3), 40 mg: 9.8 (4.1), 80 mg: 10.4 (3.6).

Continued TD improvements were observed in the KINECT-3 extension study, with approximately a 39% reduction in TD severity observed at Week 48 with INGREZZA 80 mg.24,27§ In clinical studies, INGREZZA was generally well tolerated across a broad range of adult TD patients. The most common side effect of INGREZZA in people with TD is somnolence.24

The FDA approval of INGREZZA SPRINKLE was supported by chemistry, manufacturing and controls information and data demonstrating the bioequivalence and tolerability of INGREZZA SPRINKLE compared with currently approved INGREZZA capsules.

A Case for Increased Vigilance Among Advanced Practice Providers

Recognizing and routinely assessing TD in clinical practice is critically important for those living with the condition, as TD can affect many aspects of life beyond movement. Advanced practice providers, regardless of specialty, can help increase rates of timely diagnosis of TD, as well as elicit the full measure of the impact of TD from a social, emotional and functional perspective. Treatment options exist to help reduce the uncontrolled movements of TD, with VMAT2 inhibitors recommended as first-line treatment.

For more information, please visit INGREZZAHCP.com.

*Estimated from a 2014 analysis of prescriptions and incidence rates.

†Based on in vitro VMAT2 binding affinity of dihydrotetrabenazine (HTBZ) metabolites and INGREZZA’s primary active metabolite, (+)-α-HTBZ. The clinical significance of in vitro data is unknown and is not meant to imply clinical outcomes.

‡In a post hoc analysis of the primary efficacy endpoint of patients randomized to INGREZZA 80 mg at baseline through Week 6.

§In a post hoc analysis that included patients randomized to INGREZZA 80 mg at baseline and those who were rerandomized to INGREZZA 80 mg at Week 6 (n = 65).

Important Information

INDICATION & USAGE

INGREZZA® (valbenazine) capsules and INGREZZA® SPRINKLE (valbenazine) capsules are indicated in adults for the treatment of tardive dyskinesia and for the treatment of chorea associated with Huntington’s disease.

IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION

Depression and Suicidality in Patients with Huntington’s Disease: VMAT2 inhibitors, including INGREZZA and INGREZZA SPRINKLE, can increase the risk of depression and suicidal thoughts and behavior (suicidality) in patients with Huntington’s disease. Balance the risks of depression and suicidality with the clinical need for treatment of chorea. Closely monitor patients for the emergence or worsening of depression, suicidal ideation, or unusual changes in behavior. Inform patients, their caregivers, and families of the risk of depression and suicidal ideation and behavior and instruct them to report behaviors of concern promptly to the treating physician. Exercise caution when treating patients with a history of depression or prior suicide attempts or ideation, which are increased in frequency in patients with Huntington’s disease.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

INGREZZA and INGREZZA SPRINKLE are contraindicated in patients with a history of hypersensitivity to valbenazine or any components of INGREZZA or INGREZZA SPRINKLE.

WARNINGS & PRECAUTIONS

Hypersensitivity Reactions

Hypersensitivity reactions, including cases of angioedema involving the larynx, glottis, lips, and eyelids, have been reported in patients after taking the first or subsequent doses of INGREZZA. Angioedema associated with laryngeal edema can be fatal. If any of these reactions occur, discontinue INGREZZA or INGREZZA SPRINKLE.

Somnolence and Sedation

INGREZZA and INGREZZA SPRINKLE can cause somnolence and sedation. Patients should not perform activities requiring mental alertness such as operating a motor vehicle or operating hazardous machinery until they know how they will be affected by INGREZZA or INGREZZA SPRINKLE.

QT Prolongation

INGREZZA and INGREZZA SPRINKLE may prolong the QT interval, although the degree of QT prolongation is not clinically significant at concentrations expected with recommended dosing. INGREZZA and INGREZZA SPRINKLE should be avoided in patients with congenital long QT syndrome or with arrhythmias associated with a prolonged QT interval. For patients at increased risk of a prolonged QT interval, assess the QT interval before increasing the dosage.

Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome

A potentially fatal symptom complex referred to as Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS) has been reported in association with drugs that reduce dopaminergic transmission, including INGREZZA. The management of NMS should include immediate discontinuation of INGREZZA or INGREZZA SPRINKLE, intensive symptomatic treatment and medical monitoring, and treatment of any concomitant serious medical problems. If treatment with INGREZZA or INGREZZA SPRINKLE is needed after recovery from NMS, patients should be monitored for signs of recurrence.

Parkinsonism

INGREZZA and INGREZZA SPRINKLE may cause parkinsonism. Parkinsonism has also been observed with other VMAT2 inhibitors. Reduce the dose or discontinue INGREZZA or INGREZZA SPRINKLE treatment in patients who develop clinically significant parkinson-like signs or symptoms.

ADVERSE REACTIONS

The most common adverse reaction in patients with tardive dyskinesia (≥5% and twice the rate of placebo) is somnolence.

The most common adverse reactions in patients with chorea associated with Huntington’s disease (≥5% and twice the rate of placebo) are somnolence/lethargy/sedation, urticaria, rash, and insomnia.

You are encouraged to report negative side effects of prescription drugs to the FDA. Visit MedWatch at www.fda.gov/medwatch or call 1-800-FDA-1088.

Dosage Forms and Strengths: INGREZZA and INGREZZA SPRINKLE are available in 40 mg, 60 mg, and 80 mg capsules.

Please see INGREZZA full Prescribing Information, including Boxed Warning.

This article was developed and sponsored in collaboration with Neurocrine Biosciences, Inc. Amy LaCouture, RN, BSN, PMHNP-BC and Linda Trinh, DNP, MPH, FNP-C, PMHNP-BC have been compensated by Neurocrine Biosciences, Inc. to author this article and share their perspectives.

References

- McEvoy J, Gandhi SK, Rizio AA, et al. Effect of tardive dyskinesia on quality of life in patients with bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, and schizophrenia. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(12):3303-3312. doi:10.1007/s11136-019-02269-8

- Carbon M, Hsieh CH, Kane JM, Correll CU. Tardive dyskinesia prevalence in the period of second-generation antipsychotic use: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(3):e264-e278. doi:10.4088/JCP.16r10832

- Woerner MG, Alvir JM, Saltz BL, Lieberman JA, Kane JM. Prospective study of tardive dyskinesia in the elderly: rates and risk factors. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(11):1521-1528. doi:10.1176/ajp.155.11.1521

- Miller DD, McEvoy JP, Davis SM, et al. Clinical correlates of tardive dyskinesia in schizophrenia: baseline data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial. Schizophr Res. 2005;80(1):33-43. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2005.07.034

- Turrone P, Seeman MV, Silvestri S. Estrogen receptor activation and tardive dyskinesia. Can J Psychiatry. 2000;45(3):288-290. doi:10.1177/070674370004500310

- Casey DE. Affective disorders and tardive dyskinesia. Encephale. 1988;14(Spec Issue):221-226.

- Divac N, Prostran M, Jakovcevski I, Cerovac N. Second-generation antipsychotics and extrapyramidal adverse effects. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:656370. doi:10.1155/2014/656370

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2023.

- Caroff SN, Hurford I, Lybrand J, Campbell EC. Movement disorders induced by antipsychotic drugs: implications of the CATIE schizophrenia trial. Neurol Clin. 2011;29(1):127-148. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2010.10.002

- Hauser RA, Meyer JM, Factor SA, et al. Differentiating tardive dyskinesia: a video-based review of antipsychotic-induced movement disorders in clinical practice. CNS Spectr. 2022;27(2):208-217. doi:10.1017/S109285292000200X

- Tarsy D. Tardive dyskinesia. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2000;2(3):205-214. doi:10.1007/s11940-000-0003-4

- Jackson R, Brams MN, Citrome L, et al. Assessment of the impact of tardive dyskinesia in clinical practice: consensus panel recommendations. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2021;17:1589-1597. doi:10.2147/NDT.S310605

- Tanner CM, Caroff SN, Cutler AJ, et al. Impact of possible tardive dyskinesia on physical wellness and social functioning: results from the real-world RE-KINECT study. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2023;7(1):21. doi:10.1186/s41687-023-00551-5

- American Psychiatric Association. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2023.

- Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Rev. 1976. U.S. Dept. of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration, National Institute of Mental Health, Psychopharmacology Research Branch, Division of Extramural Research Programs; 1976.

- Lundt L, Jain R, Matthews D, et al. Development of a MIND-TD questionnaire as a screening tool for tardive dyskinesia. Poster presented at: Neuroscience Education Institute Congress; November 4-7, 2021; Colorado Springs, CO.

- Meyer J. Pharmacotherapy of psychosis and mania. In: Goodman & Gilman’s: The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 13th ed. McGraw Hill; 2018.

- Benztropine mesylate [package insert]. Lake Forest, IL: Akorn; 2017.

- Ward KM, Citrome L. Antipsychotic-related movement disorders: drug-induced parkinsonism vs. tardive dyskinesia-key differences in pathophysiology and clinical management. Neurol Ther. 2018;7(2):233-248. doi:10.1007/s40120-018-0105-0

- Bhidayasiri R, Jitkritsadakul O, Friedman JH, Fahn S. Updating the recommendations for treatment of tardive syndromes: a systematic review of new evidence and practical treatment algorithm. J Neurol Sci. 2018;389:67-75. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2018.02.010

- Caroff SN, Citrome L, Meyer J, et al. A modified Delphi consensus study of the screening, diagnosis, and treatment of tardive dyskinesia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(2):19cs12983. doi:10.4088/JCP.19cs12983

- Grigoriadis DE, Smith E, Hoare SRJ, Madan A, Bozigian H. Pharmacologic characterization of valbenazine (NBI-98854) and its metabolites. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2017;361(3):454-461. doi:10.1124/jpet.116.239160

- Harriott N, Hoare S, Grigoriadis D. Selectivity of valbenazine (NBI-98854) and its major metabolites on presynaptic monoamine transport. Poster presented at: Society of Biological Psychiatry Annual Meeting; May 18-20, 2017; San Diego, CA.

- INGREZZA capsules [package insert]. San Diego, CA: Neurocrine Biosciences. 2024.

- Hauser RA, Factor SA, Marder SR, et al. KINECT 3: a phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of valbenazine for tardive dyskinesia. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(5):476-484. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.16091037

- Data on file. Neurocrine Biosciences, Inc.

- Factor SA, Remington G, Comella CL, et al. The effects of valbenazine in participants with tardive dyskinesia: results of the 1-year KINECT 3 extension study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(9):1344-1350. doi:10.4088/JCP.17m11777

© 2024 Neurocrine Biosciences, Inc. All Rights Reserved. CP-VBZ-US-3062v2 11/2024

Newsletter

Receive trusted psychiatric news, expert analysis, and clinical insights — subscribe today to support your practice and your patients.