Label Me Not: Still Learning After All These Years

The world is a better place without a "tyrant of the day" taking over and cracking down with rigid rules. This and other life lessons after 40 years in psychiatry.

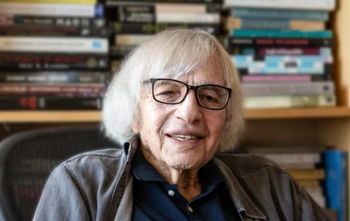

PORTRAIT OF A PSYCHIATRIST

– Series Editor, H. Steven Moffic, MD

“Be yourself. Everyone else is already taken,” Oscar Wilde said. I thought he was joking. Then I retired from psychiatry in 2012 and was free to go out in public without calling myself a psychiatrist or wearing a badge of office.

The vast field of psychiatry is divided between the urge to work with a few individuals with intense focus and the ambition to minister to large populations, as in community mental health, psychopharmacology, DSM-5, neuroscience, genetics, etc. Which feels most noble or sells the best?

I practiced all kinds of psychiatry for more than 40 years, but since retiring with aching bones in 2012, I have had time to see better how society and politics work, the dominating power of money, and it has become clearer to me that each doctor must make a choice.

[Our weekly therapy group] gradually built trust, opened up, and each caught a glimpse of himself or herself in the mirror of the Other. I thought that would last forever.

I worked in large city hospitals, clinics, and small offices in four states, always striving for the ideal of collaborative care. My last office was in Milwaukee, in a tall graceful cream-brick monument with “Historic Landmark Building, 1897” on the bronze plate out front. Inside, ten-foot ceilings had modern moldings and the front room had a fireplace with black iron grillwork.

I used the library with eight chairs in a circle, just right for the three or four groups of patients I met with weekly. We gradually built trust, each opened up, and often each caught a glimpse of himself or herself in the mirror of the Other. I thought that office would last forever.

Seven years out now with time to look back, I am elated not to dash off scripts, code, chase pre-auths, and straighten piles of papers on my desk, but I miss the faces of the many unique individuals I admired. One example is “Ray,” the 80-year-old engineer who showed me his chapter on boiler construction, mourned his wife of 55 years, and described his weekly games at the Waukesha Chess Club. Or “Mary,” the eccentric poet in a group, who wrote a piece about her hobby, “Skating as Fast as I Can.” Everyone held their breath. (DSM-5 was forgotten.) Each of us saw the fire of connection in the eyes of the Other.

I defiantly told my father I would “give medical school a trial” for one year, but after 3 days in Harkness Dorm, I knew I belonged.

I grew up in a well-off Milwaukee suburb and enjoyed a deep, clear, wild lake up north. Like Henry David Thoreau, I watched the birds, fish, and grasses there-I assumed I would carry on that religion forever. At school I yelled for all the attention I could get and tried to join the cool gangs. I thought I could fuse with some great natural force and be great, forgetting the painful quills of the other porcupines (crabby Schopenhauer’s crusty view of all society).

I can see now that I searched diligently for my “real self” and assumed it depended on which prestigious group I belonged to, my certification. As Willa Cather said, “This is happiness, to be dissolved in something truly great.”

My father was a surgeon with agile fingers and a talent for sketching. A practical man, he pushed me to go to medical school. I dragged my feet, applied to four places, and to my surprise was accepted by Yale. I defiantly told my father I would “give it a trial” for one year, but after 3 days in Harkness Dorm, I knew I belonged. There were no exams!

You had to write a thesis, but most of the faculty treated me as though I were an established researcher. My indulgent mentor, Dr Francis Black, helped me finish the thesis and publish a paper-seldom cited.

Walter Igersheimer, MD, was a shaping influence in my psychiatric residency. He was a German immigrant who looked old to me then (he was 50 in 1967).

I spent 3 hours at every dinner in endless bull sessions that flew me through multiple cultures, religions, hobbies, and nothing so dire that it didn’t end with a laugh. I married another Harkness gabber, Mary Alice, a rare woman who never failed to think of my needs, with hers being exactly equal. She was ready to fight for both.

Among others, Walter Igersheimer, MD, was a shaping influence in my psychiatric residency. He was a German immigrant who looked old to me then (he was 50 in 1967), and he ran a weekly group process session with seven of us residents. He told us he had a problem seeing, but he walked slowly down the streets of New Haven with no dog or cane. He sat in his chair at the head of the circle.

One day he didn’t arrive on time, and the wise-cracking member of our group, my friend Hugh MacIntosh, took his chair. Five minutes later, Walter Igersheimer walked slowly into the room. Everyone held his breath. Walter walked slowly to a chair at 7 o’clock and sat down quietly. We were stunned. After 3 minutes he asked, “What are people thinking?”

“You would be upset,” someone said. A long pause

“You would blow up,” someone else said. Others thought of poor Walter falling down or stumbling over to choke Hugh, who sat there smiling but quiet. Walter had the hard-won immigrant wisdom not to judge too quickly but to be interested in how each of us saw it. It was irrefutably demonstrated to me that each of us saw these brief actions differently.

Politics is temporary teams but mostly solo kickboxing, with no loyalty expected.

Each streamed his own movie. These bedrock assumptions (or transferences) came up in my own two psychoanalyses, of course, and were repeated millions of times in my interactions with all sorts of people. Walter Igersheimer showed me how families, friends, workers, religions, and politics work together-or don’t.

When I first retired, I felt an obligation to join several political action groups and advocate for “Medicare for All,” better education, etc, but was repelled by the rallies, placards, fund-raising, and plotting to shame the opponents. Politics is temporary teams but mostly solo kickboxing, with no loyalty expected.

I learned “reflective structured dialogue” from the Boston group (not unlike good therapy) and “deep-canvassing”-knocking on doors and listening to what residents want without counterarguments. I got a kick out of the talking, as in Harkness Dorm, but could see these one-shot apostles are up against cheap e-mail, millions of dollars, masses of people, and the emotional forces that surge up in large groups, like the worship of demagogues. They forget that political leaders are human, dread a possible plot against them, and will use secrets, money, or force to control “the mob.”

I talk only with priests who listen carefully and speak the truth back.

From an early age I was drawn by the call to “love the sinner and the poor” by the Catholic Church (thereby nicely including myself in the deal) but stayed away from dull sermons and endless rosaries. With more time now, I went back to look at the huge worldwide salmon run of the Church and can see more clearly the huge egos of some of the clergy. Like all large corporations-eg, HMOs, insurance companies, and professional organizations-it is a fallible corruptible bunch.

Each of us must make up our own mind about the group we want: no rosaries for me and I talk only with priests who listen carefully and speak the truth back.

I am drawn to the sense of protection in large groups. I want to express my questions and doubts and be heard but fear taking off on my own.

In the words of Chuck Palahniuk, I admit: “Nothing of me is original. I am the combined effort of everyone I have ever known.”

E. E. Cummings is listed as a poet, but was he a psychiatrist too?

Or as Jimmy Breslin said: “There have been many Jimmy Breslins because of all the people I identified with so much, turning me into them, or them into me, that I can’t easily explain one Jimmy Breslin.” (He’s no fool.) It’s like scrambled eggs, but I always want to be the special French version.

“To be nobody but yourself, in a world which is doing its best, night and day, to make you into everybody else, means to fight the hardest of battles.” (E. E. Cummings is listed as a poet, but was he a psychiatrist too?) It is up to me to decide if I fly with the flock or walk on by myself.

The way I look at it now is that 8 to 12 members is the maximum number for any group of human beings in which each of the complex individuals can thrive, keep thinking, and be heard. That is when the one leader-or even better, several-can keep track of each member, too, without anyone melting down, or the tyrant of the day taking over and cracking down with rigid rules.

Eight to 12 people can gather as in Cheers, talk honestly, be themselves, and take away a clearer idea of who they want to be. For these purposes, I have started some discussion groups (called “GrokMore Groups”), following the lead of David Bohm in On Dialogue, and hope that this helps with the isolation and division which many of my neighbors feel. I’m out of exclusive clubs and tribes with bold claims-I’d rather choose one ‘hood and tend a small garden.

Every individual must figure out who he or she is. “Be yourself. Everyone else is already taken.” Oscar hit the nail.

Dr Houghton is a retired psychiatrist. He resides in Milwaukee, WI.

Disclosures:

The author reports no conflicts of interest concerning the subject matter of this article.

Newsletter

Receive trusted psychiatric news, expert analysis, and clinical insights — subscribe today to support your practice and your patients.