Defining and Diagnosing Depression: Clinical and Patient-Oriented Perspectives

Sidney Zisook, MD, shares insights into defining depression diagnosis.

“I think the DSM gives you one sense of depression,” Sidney Zisook, MD, told attendees of the 2021 Annual Psychiatric TimesTM World CME Conference. “But I think it's very, very one dimensional. A better way of really understanding what it is to be depressed and the diagnosis is getting firsthand accounts from those who have dealt with depression.”

Zisook, director of the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) Residency Training Program, Distinguished Professor of Psychiatry at UCSD, and last year’s Educator of the Year awardee, shared insights from several famous folks about their experiences with depression. Of depression, David Foster Wallace said:

It is a level of psychic pain wholly incompatible with human life as we know it. It is a sense of radical and thoroughgoing evil not just as a feature but as the essence of conscious existence. It is a sense of poisoning that pervades the self at the self’s most elementary levels. It is a nausea of the cells and soul.

This quote, and others like it, show a sense of hopelessness, even suicidality, more than other aspects of depression, including those recognized by the DSM 5, he noted.

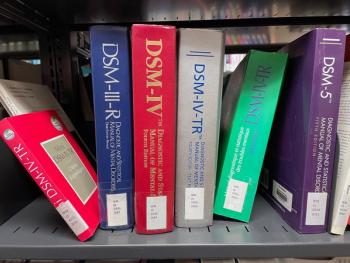

To better understand the current state of diagnosis, Zisook took attendees back in time to discuss the various iterations of depression in the DSM, from being classified as psychoneurotic disorder in DSM I in 1952 through the psychoanalytic approaches through the specifiers in DSM IV. Changes continued into DSM 5, where we now have a variety of disorders: major depressive disorder, disruptive mood dysregulation disorder, persistent depressive disorders, substance- and medication-induced depressive disorder, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, depressive disorder due to another medical condition, and other specified (or unspecified) depressive disorder.

To help illustrate the problems associated with the current system, Zisook shared 2 case examples. Ms A is a 30 year old married woman complaining of stress. Upon further exploration, you learn she has been tearful and increasingly sad since her mother received a diagnosis of cancer. She has little motivation, is overeating and gaining weight, and sleeps about 12 hours a day. She has never felt like this before.

On the other hand, Mr B is a 60 year old man who is brought to you by the police after found wandering on the Coronado Bridge. He is unshaven, slovenly, and demonstrates psychomotor retardation. He shows no interest in answering questions, but an informant tells you he has not been eating or drinking for weeks. He has expressed feeling miserable and worthless. He had a similar episode 30 years prior; he achieved full recovery after responding to electroconvulsive therapy.

“What do they have in common?” Zisook asked rhetorically. “Definitely nothing except the diagnosis of major depressive disorder—without any overlap in functioning.”

In reviewing DSM 5 criteria, he posed a few questions for the authors of DSM 6 to consider. For instance, why must symptoms last 2 weeks? “This never made much sense to me,” he said. “Somebody is undergoing a horrible situation—they lost their job, they've lost their family, they've lost their money—they've never been depressed before, and the depression is relatively mild, moderate. You don't want to label them with a major depressive disorder in 2 weeks. Give me more time to see what happens. Let them take care of some of the situations.”

“On the other hand,” Zisook added, “if they had a history of severe major depressive disorder, and for the last 2 days they're despondent, hopeless, feeling worthless, feeling suicidal, you have got to wait another 12 days to make the diagnosis.”

To better understand the diagnosis, again Zisook looked to patients. He discussed studies conducted by Mark Zimmerman, MD, and colleagues looking at what was needed for patients with depression to consider themselves in remission.1,2 The top 3 features were: positive mental health, such as optimism and self-confidence; a return to one’s usual, normal self; and a return to a usual level of functioning. Interestingly, one-quarter of respondents who were mildly symptomatic and, per HAM-D scores, not in remission considered themselves remitters. As such, they reported better quality of life, less functional impairment due to depression, higher positive mental health scores, and better coping ability.

I diagnose depression not by counting the number of symptoms for a certain number of weeks. But is the low mood persistent, is it there most of the time, has it been there for a while? It is pervasive—affecting the way you work, the way you interact with other people, the way you function, the way you parent, etc. For me that's better than the screening questionnaire or the DSM 5 criteria.

So, how does Zisook define and diagnosis depression? “There are screening instruments, which is fine for looking at depression,” he told attendees. “But I think there's nothing to substitute for clinical inquiry. And I diagnose depression not by counting the number of symptoms for a certain number of weeks. But is the low mood persistent, is it there most of the time, has it been there for a while? It is pervasive—affecting the way you work, the way you interact with other people, the way you function, the way you parent, etc. For me that's better than the screening questionnaire or the DSM 5 criteria.”

He also reminded attendees that differential diagnosis is very important, adding “Always look for bipolar disorder or general medical conditions.” Bereavement and burnout also need special attention, he explained, since those are often misdiagnosed and/or confused with depression. A careful examination of the criteria and symptoms will help to distinguish the disorders.

Zisook concluded by saying, “I think our diagnostic concepts are a work in progress in terms of helping us communicate with each other, helping us take into account what patients are saying about what it feels like to be depressed, and helping us to prescribe very personalized medications.”

Learn more about the 2021 Annual Psychiatric TimesTM World CME Conference

References

1. Zimmerman M, McGlinchey JB, Posternak MA, et al.

2. Zimmerman M, Martinez J, Attiullah N, et al.

Newsletter

Receive trusted psychiatric news, expert analysis, and clinical insights — subscribe today to support your practice and your patients.