|Slideshows|May 13, 2019

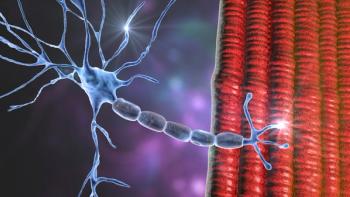

7 Ways to Treat Tardive Dyskinesia

Author(s)Chris Aiken, MD

Once thought untreatable, we now have two FDA-approved medications for TD and a handful of off-label options. More in this research update.

Advertisement

Newsletter

Receive trusted psychiatric news, expert analysis, and clinical insights — subscribe today to support your practice and your patients.

Advertisement

Latest CME

Advertisement

Advertisement

Trending on Psychiatric Times

1

Depression and Long COVID Outcomes in Women: New Data Analysis

2

Presenting Our February 2026 Theme: Bipolar Disorder

3

Investigational Psilocybin for PTSD and Ongoing Trials

4

Patterns of Propensity: A Review of Heinrichs’ How Psychiatrists Make Decisions

5