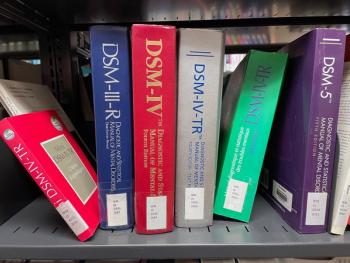

Is the Criticism of DSM-5 Misguided?

Critics of DSM-5 argue that the expansion of diagnostic criteria may increase the number of “mentally ill” individuals and/or pathologize “normal” behavior, and lead to the possibility that thousands-if not millions-of new patients will be exposed to medications which may cause more harm than good.

In 2013, the American Psychiatric Association will publish the

Much of the criticism, including that from its most vocal critic,

The American Psychological Association, the

, and the

I understand and sympathize with the critics, particularly against the DSM‘s emphasis on “user acceptability” over validity (and, in the interest of full disclosure,

First of all, let’s just state the obvious: it is impossible to write a comprehensive, scientifically valid catalog of all mental illnesses (particularly when some argue convincingly that mental illness is itself a

Thus, the DSM-5, like all DSM’s before it, will be, almost by definition,

In other words, the danger lies not in the label, but in how we use it. In fact, one might even argue that a lousy label-or a label that is so nonspecific that it applies to a broad swath of the population, including some in the “normal” part of the spectrum (wherever that may be)-may actually be beneficial, because it will be so meaningless that it will require the clinician to think more deeply about what that label is trying to convey.

As an example, consider “chronic pain,” a label frequently applied to patients and written in their charts. (Even though it’s often written as a diagnosis, it is really a symptom.) “Chronic pain” simply implies that the patient experiences pain. Nothing more. It says nothing about the origin of the pain, what exacerbates or soothes it, how long the patient has experienced it, or whether it responds to NSAIDs, opioids, acupuncture, yoga, or rest. When a new patient complains of “chronic pain” to a good pain specialist, the doctor doesn’t just write a script; he or she performs an examination, obtains a detailed history and collateral information, and treats in a manner that relieves discomfort yet minimizes side effects (and cost) to the patient.

Perhaps this is what we can do in psychiatry, even with the

Will the new diagnoses be “overused”? Probably. Will they lead to “overdrugging” of patients-the outcome that everyone fears? I guess that’s possible. But if so, the spotlight should be turned on those who do the overdrugging, not on the document that simply describes the symptoms. This may turn out to be difficult: official treatment guidelines might come out with recommendations to medicate, insurance companies may require diagnoses (or medications) in order to cover psychiatric services, and drug companies might aggressively market their products for these new indications. And there will always be doctors who cut corners, arrive at diagnoses too quickly and are eager to use dangerous medications. But these targets, ultimately, are where the anti-DSM-5 efforts should be placed, not on its

In the end, one could argue that the DSM-5 is unnecessary, premature, and flawed. Unfortunately, it simply

[Editor's Note: This article was originally posted on Dr Balt's blog at

Newsletter

Receive trusted psychiatric news, expert analysis, and clinical insights — subscribe today to support your practice and your patients.