CME

Article

Psychiatric Times

Ketamine and Psychedelics: The Journey From Magical Mystery to Informed Consent

Author(s):

In this CME article, learn more about the best practices for engaging patients in the informed consent process for psychedelic treatment and psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy.

maaramore©/AdobeStock

CATEGORY 1 CME

Premiere Date: August 20, 2023

Expiration Date: February 20, 2025

This activity offers CE credits for:

1. Physicians (CME)

2. Other

All other clinicians either will receive a CME Attendance Certificate or may choose any of the types of CE credit being offered.

ACTIVITY GOAL

The goal of this activity is to recognize the importance of informed consent in the rapidly developing psychedelic treatment landscape and to develop strategies for collaboratively engaging patients in informed consent.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After engaging with the content of this CME activity, you should be better prepared to:

-Understand the distinct points required for informed consent regarding psychedelic treatment and psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy compared with traditional psychiatric treatments.

-Understand best practices for engaging patients in the informed consent process for developing psychedelic-informed treatments.

TARGET AUDIENCE

This accredited continuing education (CE) activity is intended for psychiatrists, psychologists, primary care physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and other health care professionals who seek to improve their care for patients with mental health disorders.

ACCREDITATION/CREDIT DESIGNATION/FINANCIAL SUPPORT

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the accreditation requirements and policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) through the joint providership of Physicians’ Education Resource®, LLC, and Psychiatric Times®. Physicians’ Education Resource®, LLC, is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Physicians’ Education Resource®, LLC, designates this enduring material for a maximum of 1.5 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

This activity is funded entirely by Physicians’ Education Resource®, LLC. No commercial support was received.

OFF-LABEL DISCLOSURE/DISCLAIMER

This accredited CE activity may or may not discuss investigational, unapproved, or off-label use of drugs. Participants are advised to consult prescribing information for any products discussed. The information provided in this accredited CE activity is for continuing medical education purposes only and is not meant to substitute for the independent clinical judgment of a physician relative to diagnostic or treatment options for a specific patient’s medical condition. The opinions expressed in the content are solely those of the individual faculty members and do not reflect those of Physicians’ Education Resource®, LLC.

FACULTY, STAFF, AND PLANNERS’ DISCLOSURES AND CONFLICT OF INTEREST (COI) MITIGATION

None of the staff of Physicians’ Education Resource®, LLC, or Psychiatric Times, or the planners or the authors of this educational activity, have relevant financial relationship(s) to disclose with ineligible companies whose primary business is producing, marketing, selling, reselling, or distributing health care products used by or on patients.

For content-related questions, email us at PTEditor@mmhgroup.com. For questions concerning the accreditation of this CME activity or how to claim credit, please contact info@gotoper.com and include “Ketamine and Psychedelics: The Journey From Magical Mystery to Informed Consent” in the subject line.

HOW TO CLAIM CREDIT

Once you have read the article, please use the following URL to evaluate and request credit https://education.gotoper.com/activity/ptcme23aug. If you do not already have an account with PER® you will be prompted to create one. You must have an account to evaluate and request credit for this activity.

The Magical Mystery Tour

Is waiting to take you away

Waiting to take you away

. . .

They’ve got everything you need

Roll up for the Mystery Tour

Roll up

Satisfaction guaranteed

. . .

The Magical Mystery Tour

Is dying to take you away

Dying to take you away

Take you today

– John Lennon and Paul McCartney, “Magical Mystery Tour”

Since the 1960s, interest in the therapeutic benefits of psychedelic drugs has been periodically revived, with significant resources being invested in drug development and proof of efficacy. Sparking the current revival has been the drug ketamine, a dissociative anesthetic that also induces profound psychedelic experiences and hallucinations. There has been a groundswell of enthusiasm, interest, and investment in—and also skepticism of—the medical potential of psychedelics, as researchers have gathered data supporting the benefits of psychedelics for the treatment of emotional problems and psychiatric disorders.1,2

Such favorable data sparked authorized clinical trials of psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) for posttraumatic stress disorder, with the US FDA designating these molecules as breakthrough drugs. Although there is growing optimism that the FDA and the pharmaceutical industry will be open to further research on the medical applications of psychedelics,3 use of and even research on many of these drugs currently is unlawful for the most part, as these drugs are designated as Schedule I controlled substances. However, this will likely change as the data accumulate.

Numerous studies already show great benefits of psychedelic treatment for a variety of conditions, including depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders, with minimal harms.2 The psychedelic and empathogen MDMA also has evidence that it may be safer and more effective than currently available first-line pharmacologic agents.1 Early studies also show promise for postpartum depression, a difficult-to-treat mental health condition with high morbidity.4

Finally, psychedelics may even have a role outside mental health. Low-powered studies and anecdotal reports over the past 50 years have shown psychedelics to be helpful for cancer pain, phantom limb pain, and cluster headaches. Growing evidence and putative mechanisms of action (ie, brain connectivity, neuroinflammatory, and proimmunomodulatory responses) indicate that psychedelics may be helpful in treating chronic pain conditions.5

The growing interest in dissociative and hallucinogenic drugs for the treatment of psychiatric disorders presents special challenges for clinicians when it comes to obtaining informed consent to trials of such medications. Fully informed consent includes ongoing assessment of a patient’s understanding of the risks and benefits of the proposed treatment and of relevant alternatives, including deferred treatment and no treatment at all. It requires engaging the patient in dynamic, collaborative decision-making with feedback and adjustment.6 An important component of the informed-consent process is a shared acknowledgment of uncertainty, as the physician empathizes with the patient’s wish for certainty so that patient and physician can work together to turn uncertainty into manageable probabilities.7

Treatment with psychedelics presents uncertainties above and beyond those generally inherent in the course of illness and effects of treatment. First, there is the variable, and not always well defined, legal and regulatory status of these drugs in different jurisdictions. Second, legal prohibitions growing out of societal mistrust of psychedelics have inhibited the research that might lead to increased effectiveness and safety. As a result, to varying degrees, there is insufficient awareness of short-term and especially long-term risks and benefits, increasing the likelihood of unfavorable clinical outcomes and malpractice liability.8

Finally, as is regularly observed in the recreational use of psychedelics, there is added variability in the interaction between the substance and the individual user. The model of drug effects as a function of the substance, mental set, and setting was developed by Norman Zinberg, MD, in the Cambridge, Massachusetts, vicinity of Timothy Leary, where Zinberg practiced psychiatry and where psychedelics were promoted as a “magical mystery tour” (“everything you need,” “satisfaction guaranteed,” “dying to take you away”).9

In clinical treatment, the setting, which encompasses the therapeutic alliance as well as the patient’s life situation, influences the mental set the patient brings to the medication and ultimately (along with the usual physiological variables) the effect the substance has on the patient. As with any form of treatment, and especially with psychotropic medications, one size does not fit all.

Hallucinogens are a diverse group of drugs that alter an individual’s awareness of their surroundings, as well as their thoughts and feelings. Psychedelics are psychoactive substances that alter perception and mood, affecting numerous cognitive processes. Empathogens (or entactogens) are psychoactive drugs that promote empathy or sympathy (Table 1) and may have acute anxiolytic effects leading to profound states of introspection and personal reflection. In this article, we discuss all these medications under the rubric of psychedelics.10

Table 1. Feelings of Empathy or Sympathy Promoted by Empathogens

Obtaining Informed Consent

Regardless of their final form of administration, once psychedelic medications are approved and recommended as treatment, a psychiatrist has an ethical obligation to obtain informed consent from the patient regarding the drugs. This is a fundamental ethical responsibility that is also a legal duty. Failure to obtain informed consent is one of the most common allegations in medical malpractice litigation.11

Particularly important when considering psychedelic-informed psychotherapy is the way in which the informed consent process affects the relationship between the patient and the psychiatrist. The psychiatrist can utilize the informed consent process to improve the therapeutic alliance. The therapeutic alliance, together with the physical space of therapy, creates a holding environment in which a patient can feel supported and safe, allowing for the maximum efficacy of treatment. If informed consent for psychedelic therapy is obtained appropriately—that is, collaboratively and dynamically with the patient—it provides an opportunity not only to enhance a patient’s autonomy, but also to improve this holding environment, maximizing placebo benefits and reducing nocebo risks of treatment.12 As such, a robust yet tactful informed consent process contributes to the patient’s mindset, ultimately enhancing their interaction and experience with the psychedelic and the treatment process.

Informed consent requires the treatment provider to spend time educating the patient to be a partner in decision-making, which generally consists of clinical, ethical, legal, and risk-management dimensions. Although different standards for informed consent exist, the reasonable patient standard is most frequently used in the United States,13 as elucidated by the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia in Canterbury v Spence, 464 F2d 772 (DC Cir 1972).

The questions raised by the reasonable patient standard currently do not have clear answers. We do not know what a reasonable patient may want to know about psychedelic-informed therapy, the potential dangers of which are still being studied. Resolving these questions remains complicated. Many physicians believe psychedelics can be very helpful, while others believe expanded use of these drugs will be harmful.14 Many have no meaningful opinion, as they have little experience with this area of science and medicine.

A similar situation exists with cannabis. Although most Americans support the legalization of medical marijuana, physicians remain divided on this area, often due to lack of knowledge. As a result, they are unable to meaningfully advise patients. Many patients want to discuss marijuana with their physicians but feel they cannot bring it up because the medical community, as a whole, has been dismissive of the issue. Now physicians are trying to play catch-up and learn about an area in which their patients may have much greater knowledge.15

Truly informed consent may be impossible if a patient feels they cannot bring up or discuss alternative treatments with a doctor. To mitigate this challenge, psychiatrists must continue to educate themselves on the development of emerging treatments.

Results of research on psychedelic-assisted treatment have yet to formulate definitive protocols or to identify which patients may benefit most and which may be at the greatest risk of harm. This makes it difficult to educate physicians on comparisons between alternative treatments and no treatment, which is a key component of informed consent. Since our scientific understanding is still developing, many of the risks may not even be elucidated. Even newer information confirmed in the literature may not be widely known and practiced. For example, ketamine is known to have abuse potential and to cause dependence.16,17 However, despite the lack of evidence indicating that repeated low doses of ketamine will not cause addiction, there continue to be claims that low-dose ketamine is nonaddictive and safe.18

Psychedelic treatments present another unique challenge. Although neurobiological mechanisms have been proposed for the effects of drugs like ketamine, psychedelics may produce much of their effect through mystical and transformative experiences. If informed consent requires explaining the proposed therapy, there may be serious challenges in adequately explaining the nature of psychedelic therapy to a patient, particularly one in a vulnerable state of mind associated with a disorder such as severe treatment-resistant depression or a significant substance use disorder.19

Additionally, psychedelic-induced euphoria, coupled with the dramatic increase in prosocial feelings with empathogens (such as MDMA), makes a patient vulnerable to boundary violations. Since patients in altered states of consciousness are especially open to suggestion, manipulation, and even exploitation, the heightened risk of boundary violation is unique to psychedelic-assisted therapy compared with more traditional psychiatric treatments.20 This potential for boundary violation requires special consideration for appropriate informed consent, as the risk is likely to be misunderstood or underappreciated by both therapist and patient.

Given how the personalized nature of one’s subjective experience with psilocybin impacts its effect,21 it is conceivable that clinicians cannot adequately understand or explain the process without having undergone such therapy themselves. Doctors typically do not need to have had a treatment personally to inform a patient about its risks. However, psychedelics do not have the extensive research literature of many treatments, and informing a patient about the risks of entering an “altered state of consciousness” seems difficult to do, given the subjectivity of the experience. If the clinician has not experienced such a state, it may be impossible for them to truly understand its implications. However, at this time, given that possession of psychedelics remains a federal crime, psychiatrists have no reliable mechanism to obtain such experience.

Finally, in our own clinical experience, patients who seek treatment with ketamine or psychedelics may constitute a select population with a high incidence of prior street hallucinogen use. The informed consent process should explore any prior experiences with hallucinogens, expectations that those experiences may engender, and the added risks of mixing ketamine with increasingly available and legalized street hallucinogens.22

Assessing Understanding of Risk

Although much empirical support exists for the benefits of ketamine and psychedelics, clinical concerns remain regarding the use of these drugs in treatment. As seen with cannabis, enthusiastic academics and media promotion often oversell the benefits of these chemicals, without the requisite scientific evidence.23,24 At the same time, individuals often ignore the potential for adverse effects.

Unlike many medications studied for self- administration at home, to date, the evidence base for psychedelics has been developed in the context of trained clinicians providing psychotherapy, with experiences pre- and post administration being relevant to treatment.24 If psychedelics are approved by the FDA for use with therapy, off-label advertising and dosing will be a significant concern. With the lay interest in psychedelics and the recreational benefit of these medications, it is possible that patients will seek prescriptions for off-label indications with the intention of using them at home. At present, studies of unstructured and unguided use at home by patients are minimal, and the risks are less understood, relative to the use of the drugs in clinical settings.

With psychedelics, psychological sequelae tend to be of greater concern than physical adverse effects. Although mystical and transformative experiences may be essential to the therapeutic effect, there also exists potential for negative outcomes, “bad trips,” and challenging psychological experiences25; one survey showed that 1 in 10 users of psilocybin put themselves or others at risk of physical harm.26 Many sought treatment for enduring psychological symptoms due to the bad trip, with numerous cases of attempted suicide and enduring psychosis related to psilocybin use.26 Although it has been suggested that even a negative experience with psilocybin can ultimately be used as a catalyst for personal growth,27 this is likely best achieved in a supervised setting with a mental health professional guiding treatment through the negative experience.

Clinically, psychedelics are used primarily for treatment of affective disorders. Patients suffering from these disorders may manifest affectively based incapacity to give informed consent even when they retain cognitive capacity.28 They also are especially susceptible to some degree of magical thinking, by which they may assign outsized potency (for good or ill) to a recommended medication.29 The risks of such magical thinking are particularly exacerbated when pharmaceuticals are extravagantly promoted by advocates who do not necessarily have a medical background. As a result, many patients will likely request treatment with psychedelics, hoping for a quick and easy cure, while neglecting to explore potential alternatives such as psychotherapy and currently approved medications.

These dynamics make the therapeutic alliance and the informed-consent process all the more vital to creating a setting conducive to successful treatment and risk management. For example, one needs to consider what the substance means to the patient. If the patient sees treatment with psychedelics as a desperate last hope in the face of hopelessness, such an unrealistic expectation needs to be addressed before the medication is administered, followed by appropriate monitoring and follow-up. Otherwise, the benefits of the treatment may be outweighed by risks, some of which are listed in Table 2. A heightened risk of suicidality must then be taken into account.30

Table 2. Potential Risks That May Outweigh the Benefits of Treatment

This concern is exemplified by psilocybin’s demonstrated benefit in alleviating anxiety and fear related to death and dying.31,32 Although psychedelics relieve these painful feelings, the mechanism by which they do so remains unclear. Researchers do not know whether psilocybin induces genuine insights about life and death or provides false hope, potentially “simply foisting a comforting delusion on the sick and dying.”33 To many patients, this distinction may not matter if their goal is to alleviate personal distress. It has also been argued that the understanding of psychedelic experiences is relatively unimportant compared with the experiences’ potential therapeutic benefit.34 However, on the contrary, clinicians need to be mindful of the incomplete current understanding of these treatments regarding not only the mechanism resulting in benefit but also the potential for risk.

Decision-making that is hyperfocused on hallucinogens creates additional risks in treatment, which include failing to consider alternatives such as medications and psychotherapy, as well as established interventions like electroconvulsive therapy. This is similar to any situation in which a doctor or patient becomes focused on only 1 treatment pathway. Neglecting alternatives can lead a patient to develop an overreliance on the psychedelic, believing it is the only effective treatment path and minimizing other viable options. Ultimately, if a clinician is not careful, they may foster this belief system, creating a risk of reducing rather than increasing patient agency.

There are not yet robust studies on the long-term abuse and dependence potential of psychedelics, nor are there standards or treatment guidelines that might inform clinicians about how to obtain informed consent to psychedelic-assisted therapy. Without adequate understanding of long-term risks and without patients’ fully informed consent, long-term adoption of these therapies could recapitulate the history of the opioid epidemic, whereby the health care system developed an overreliance on a quick, simplistic answer to complex physical and mental health needs.35

Failure of the Informed Consent Process

Currently, there are no clear consequences for the failure of the informed consent process. Although several entities provide training and certifications for psychedelic therapy, no consensus exists among the certifying bodies as to what constitutes education and qualified experience. In short, no process has emerged to qualify or certify those who run the certifying bodies. Likewise, it is unclear who would investigate adverse outcomes related to poor informed consent. For example, what happens if a patient who was not screened for bipolar disorder becomes manic during therapy? What happens if, due to a “bad trip,” a patient develops severe psychological distress with long-lasting consequences?

Recently, the shuttering of a chain of clinics using ketamine therapy made the news. Does the failure of the clinic to continue to operate or provide services constitute patient abandonment, especially if those services are not otherwise readily available in the community? The concern for patient abandonment is heightened if this risk is not addressed in an informed consent process.

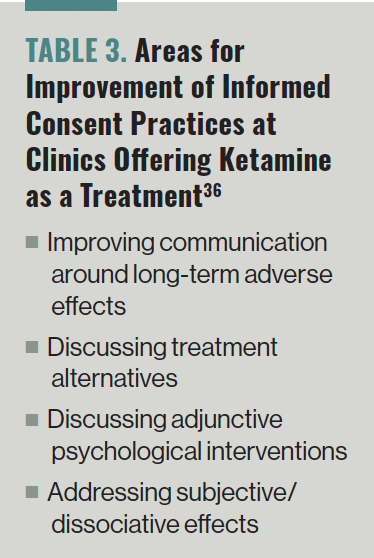

One study reviewed the informed consent practices of clinics that offer ketamine as a treatment for psychiatric disorders and found that the clinics varied significantly in their approaches to informed consent. The authors found numerous areas for improvement (Table 336); indeed, all the informed consent documents were assessed to have “poor readability.”36

Table 3. Areas for Improvement of Informed Consent Practices at Clinics Offering Ketamine as a Treatment36

When problems occur, a previously uninformed patient who has quick-fix or panacea-like hopes that do not materialize may pursue malpractice claims. Patients do not file lawsuits simply because of a bad outcome, but a common litigation trigger is the feeling that they were not given all the information that was available.37

However, it is not even clear that ketamine- or psychedelic-informed psychotherapy constitutes the practice of medicine in all jurisdictions, as the therapy provider is not necessarily the one prescribing the drug and, in some states, the drugs are decriminalized. There is strong opposition to the medicalization of psychedelics and to pharmaceutical industry “control” and monetization of drugs that already exist. Some hope that access to psychedelics will parallel access to cannabis, with consumers having the final decision about whether they wish to use a drug for any personal reason or simply to feel “better,” rather than for specified physical or emotional symptoms or diagnoses.

Nonetheless, ketamine and psychedelics are drugs whose psychological and physiological effects are complex and still poorly understood. A patient has a right to know how, according to the best current knowledge, treatment with these drugs might interact with preexisting medical and psychological conditions, as well as with other medications and substances the patient may be using. Becoming knowledgeable about these interactions and risks, and learning how to obtain an adequate history, requires training and supervised experience.

Physicians—who have formal education in biochemistry, pharmacology, and clinical medicine—collectively have decades of experience prescribing most psychiatric medications. This background does not extend to psychedelics, which remain federally criminalized and have long been regarded as dangerous and lacking in therapeutic value. Most current advocates and practitioners of psychedelic therapy have no medical background and may not even have formal mental health training. As these treatments become more popular and eventually are legalized, patients deserve to have ethical practitioners who appropriately understand the medical risks of psychedelic therapy, whether they be physicians with additional training in psychedelics or nonmedical practitioners who undergo rigorous training in these areas.

Ultimately, the challenges of informed consent should not be a justification for avoiding necessary treatment. Rather, they should spur clinicians to learn more about the treatments they are recommending and to fully engage patients in a dynamic and collaborative decision-making process that requires feedback and adjustment.6 Psychiatry does not need to adopt therapeutic nihilism, paralyzed by the uncertainty of potentially life-changing treatments—but neither should it fall prey to therapeutic overconfidence, denying very real shortcomings in the current understanding of psychedelics.38

Concluding Thoughts

Psychedelics have entered psychiatric practice and are likely here to stay. It may not be very long before psychedelic-assisted treatments become legal and commonplace. Although a growing body of evidence supports the benefits of psychedelics for several mental health conditions (particularly in treatment-refractory cases), numerous issues remain that have not been worked out. Although regulations need to be clearer, individual physicians can improve quality through the practice of robust yet tactful informed consent.

Beyond being an ethical and professional duty, informed consent in practice contributes to the safety of the clinical setting via the therapeutic alliance. Engaging in a collaborative, dynamic informed consent process can enhance the holding environment for psychedelic therapy, improving the patient’s mindset and leading to a beneficial placebo response to a substance while minimizing susceptibility to nocebo effects.

We believe that all psychiatrists have a professional obligation to remain up-to-date on treatment developments and to be ready to appropriately recommend and coordinate care with ketamine and psychedelics when indicated. Psychedelics are being studied for numerous diagnoses, and emerging data support psychedelic treatment for some conditions more than others. Although a complete discussion on the benefits and risks of psychedelic treatment for each diagnosis is outside the scope of this article, psychiatrists must be aware of this literature if they plan to recommend psychedelic treatment, as the indication may affect both the potential benefits and the potential harms.

If a psychiatrist directly endeavors to utilize psychedelic-assisted therapy, it is essential to understand the aspects of informed consent that must be considered. We have striven to explore the challenges that may arise in helping patients truly understand such treatment, which may often be requested. Further research is needed not only into potential beneficial and adverse psychological effects of psychedelic-assisted therapy, but also into how patients understand these benefits and risks and how psychiatrists can adequately explain them.

Dr MacIntyre is a faculty member at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), and a psychiatrist at the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System of Greater Los Angeles, where he is site director for the UCLA forensic psychiatry fellowship. Dr Nair is a volunteer clinical faculty member at UCLA, where he is actively involved in the forensic psychiatry fellowship program. Dr Bursztajn is a faculty member at Harvard Medical School and a practicing psychiatrist in Cambridge, Massachusetts, with a longstanding interest in decision-making under conditions of trauma and uncertainty.

References

1. Krystal JH. Ketamine and the potential role for rapid-acting antidepressant medications. Swiss Med Wkly. 2007;137(15-16):215-216.

2. Griffiths RR, Grob CS. Hallucinogens as medicine. Sci Am. 2010;303(6):76-79.

3. Lamkin M. Prescription psychedelics: the road from FDA approval to clinical practice. Am J Med. 2022;135(1):15-16.

4. Szuster RR. Asclepius revisited – ancient myth and 21st-century psychedelic medicine. JAMA. 2022;327(19):1851-1852.

5. Bogenschutz MP, Ross S, Bhatt S, et al. Percentage of heavy drinking days following psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy vs placebo in the treatment of adult patients with alcohol use disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79(10):953-962. Published correction appears in JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79(11):1141.

6. Bursztajn H, Feinbloom R, Hamm R, Brodsky A. Medical Choices, Medical Chances: How Patients, Families, and Physicians Can Cope With Uncertainty. Delacorte; 1981. Routledge; 1990.

7. Gutheil TG, Bursztajn H, Brodsky A. Malpractice prevention through the sharing of uncertainty. informed consent and the therapeutic alliance. N Engl J Med. 1984;311(1):49-51.

8. Madras BK. Psilocybin in treatment-resistant depression. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(18):1708-1709.

9. Zinberg N. Drug, Set, and Setting: The Basis for Controlled Intoxicant Use. Yale University Press; 1984.

10. Drug fact sheet: hallucinogens. Department of Justice/Drug Enforcement Administration. April 1, 2020. Accessed June 23, 2023. https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2020-06/Hallucinogens-2020.pdf

11. Frierson RL, Joshi KG. Malpractice law and psychiatry: an overview. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ). 2019;17(4):332-336.

12. Weimer K, Colloca L, Enck P. Placebo effects in psychiatry: mediators and moderators. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(3):246-257.

13. Gopal AA, Cosgrove L, Shuv-Ami I, et al. Dynamic informed consent processes vital for treatment with antidepressants. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2012;35(5-6):392-397.

14. Barnett BS, Siu WO, Pope HG Jr. A survey of American psychiatrists’ attitudes toward classic hallucinogens. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2018;206(6):476-480.

15. Grinspoon P. Medical marijuana. Harvard Health Blog. April 10, 2020. Accessed May 26, 2023. https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/medical-marijuana-2018011513085

16. Orhurhu VJ, Vashisht R, Claus LE, Cohen SP. Ketamine toxicity. StatPearls. January 30, 2023. Accessed May 26, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541087/

17. Liu Y, Lin D, Wu B, Zhou W. Ketamine abuse potential and use disorder. Brain Res Bull. 2016;126(Pt 1):68-73.

18. Ho RCM, Zhang MW. Ketamine as a rapid antidepressant: the debate and implications. BJPsych Advances. 2016;22(4):222-233.

19. Lieberman JA. Back to the future – the therapeutic potential of psychedelic drugs. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(15):1460-1461.

20. Jaster AM. Issues of patient safety and ethical violations in psychedelic therapy. Psychedelic Science Review. August 19, 2022. Accessed May 26, 2023. https://psychedelicreview.com/issues-of-patient-safety-and-ethical-violations-in-psychedelic-therapy/

21. Malone TC, Mennenga SE, Guss J, et al. Individual experiences in four cancer patients following psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:256.

22. Pilecki B, Luoma JB, Bathje GJ, et al. Ethical and legal issues in psychedelic harm reduction and integration therapy. Harm Reduct J. 2021;18(1):40.

23. Boehnke KF, Davis AK, McAfee J. Applying lessons from cannabis to the psychedelic highway: buckle up and build infrastructure. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(6):e221618.

24. Siegel JS, Daily JE, Perry DA, Nicol GE. Psychedelic drug legislative reform and legalization in the US. JAMA Psychiatry. 2023;80(1):77-83.

25. Bienemann B, Stamato Ruschel N, Campos ML, et al. Self-reported negative outcomes of psilocybin users: a quantitative textual analysis. PLoS One. 2020;15(2):e0229067.

26. Carbonaro TM, Bradstreet MP, Barrett FS, et al. Survey study of challenging experiences after ingesting psilocybin mushrooms: acute and enduring positive and negative consequences. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1268-1278.

27. Gashi L, Sandberg S, Pedersen W. Making “bad trips” good: how users of psychedelics narratively transform challenging trips into valuable experiences. Int J Drug Policy. 2021;87:102997. Published correction appears in Int J Drug Policy. 2021;93:103183.

28. Bursztajn HJ, Harding HP Jr, Gutheil TG, Brodsky A. Beyond cognition: the role of disordered affective states in impairing competence to consent to treatment. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1991;19(4):383-388.

29. Bursztajn H, Gutheil TG, Brodsky A, Swagerty EL. “Magical thinking,” suicide, and malpractice litigation. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1988;16(4):369-377.

30. Coletsos IC, Bursztajn HJ. Suicide, evaluating risk for. In: Domino FJ, Baldor RA, Barry KA, Golding J, Stephens MB, eds. The 5-Minute Clinical Consult 2023. 31st ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2022.

31. Sweeney MM, Nayak S, Hurwitz ES, et al. Comparison of psychedelic and near-death or other non-ordinary experiences in changing attitudes about death and dying. PLoS One. 2022;17(8):e0271926.

32. Yu C-L, Yang F-C, Yang S-N, et al. Psilocybin for end-of-life anxiety symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Investig. 2021;18(10):958-967.

33. Letheby C. The epistemic innocence of psychedelic states. Conscious Cogn. 2016;39:28-37.

34. Flanagan O, Graham G. Truth and sanity: positive illusions, spiritual delusions, and metaphysical hallucinations. In: Poland J, Tekin S, eds. Extraordinary Science and Psychiatry: Responses to the Crisis in Mental Health Research. MIT Press; 2017.

35. Dasgupta N, Beletsky L, Ciccarone D. Opioid crisis: no easy fix to its social and economic determinants. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(2):182-186.

36. Mathai DS, Lee SM, Mora V, et al. Mapping consent practices for outpatient psychiatric use of ketamine. J Affect Disord. 2022;312:113-121.

37. Huntington B, Kuhn N. Communication gaffes: a root cause of malpractice claims. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2003;16(2):157-161; discussion 161.

38. Gopal A, Pirakitikulr D, Bursztajn HJ. Informed consent in neuropsychosocialpharmacology. Psychiatric Times. 2005;22(13):59-63.

Newsletter

Receive trusted psychiatric news, expert analysis, and clinical insights — subscribe today to support your practice and your patients.