Publication

Article

Psychiatric Times

Course and Treatment Outcomes of ADHD

Author(s):

What factors are involved in parents’ decision to begin medication treatment for a child with ADHD? An overview of studies that provide clinically relevant information related to the course and treatment outcomes of ADHD in children and adolescents.

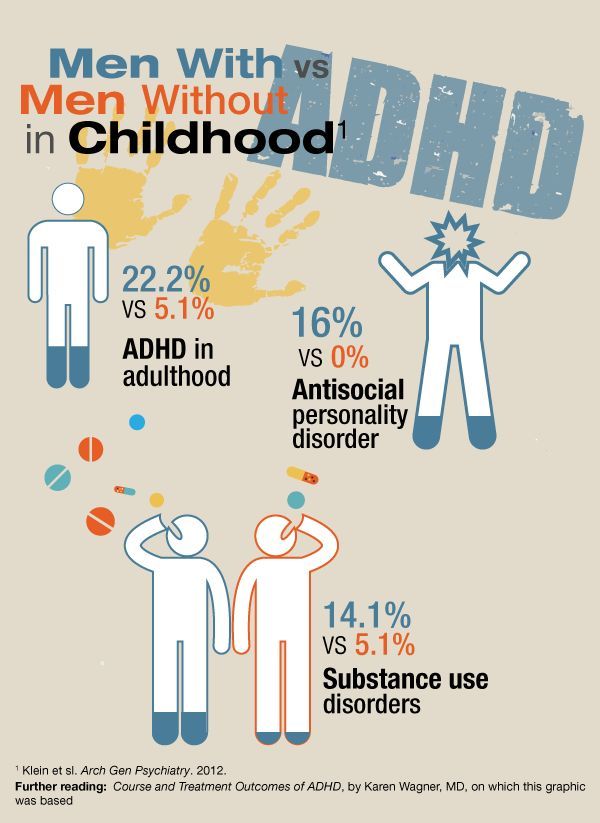

Infographic: Men With Versus Men Without ADHD in Childhood

Recent studies provide clinically relevant information related to the course and treatment outcomes of ADHD in children and adolescents. In the longest controlled prospective study of childhood ADHD, Klein and colleagues1 (2012) examined clinical and functional outcomes in adulthood. Study participants were boys aged 6 to 12 years (mean age 8.3 years) who had ADHD at the start of the study. The control group consisted of boys without ADHD; 135 men with ADHD in childhood (65.2% of original sample) and 136 men without ADHD (76.4% of original sample) participated in the follow up study. The follow up period was 33 years with a mean age of 41 years.

Study results showed that compared with men without childhood ADHD, men with childhood ADHD had higher rates of ongoing ADHD (22.2% vs 5.1%), antisocial personality disorder (16.3% vs 0%), substance use disorders (14.1% vs 5.1%), and psychiatric hospitalizations (24.4% vs 6.6%). There were no differences between these groups in prevalence of alcohol disorders, mood disorders, and anxiety disorders. Men with childhood ADHD also had lower educational levels (mean 2.5 less years), lower occupational achievement, lower socioeconomic status, lower social functioning, higher divorce rates, more incarcerations, and higher mortality. Based on these long-term outcomes, the investigators emphasize the importance of monitoring and treating children with ADHD. (see Infographic)

Criminal behavior

ADHD has been associated with criminal behavior. Lichtenstein and colleagues2 examined the effects of treatment with ADHD medication on criminality. Information was obtained from the Swedish national registers on 25,656 patients who had a diagnosis of ADHD, their medication treatment and criminal convictions. The rates of criminal behavior were compared when the patients were being treated for ADHD and when these same patients were not being treated for ADHD.

For men with ADHD, there was a 32% reduction in criminality and for women with ADHD there was a 41% reduction in criminality when receiving medication. The rates of criminality were the same whether the ADHD medication was a stimulant or nonstimulant. The authors conclude that medication treatment for ADHD may reduce the risk for criminal behavior in individuals with ADHD.

Cigarette smoking

Cigarette smoking is also associated with ADHD. Hammerness and colleagues3 conducted a study of 154 adolescents with ADHD to determine whether stimulants reduce the risk for cigarette smoking. The comparison groups were a naturalistic sample of ADHD and non-ADHD youth. Cigarette smoking was assessed by a self-report questionnaire that measured smoking behavior and physiological dependence to nicotine. Urine assays for cotinine, a metabolite of nicotine, were obtained for adolescents in the clinical trial. Doses of extended-release methylphenidate were based on clinical response and the mean endpoint dose was 61 mg daily.

The rate of smoking in youths who received stimulant treatment was significantly lower than in the unmedicated ADHD comparison group (7.1% vs 19.6%). The rate of smoking in the stimulant treated adolescents was similar to the comparison group of non-ADHD youth and ADHD youth currently on medication (7.1% vs 8.0% vs 10.9%). The investigators recognize that these positive results are preliminary and recommend a randomized clinical trial.

Nonstimulant treatment

There is a large evidence base supporting the efficacy of stimulant treatment for children and adolescents with ADHD, however some parents prefer nonmedication treatment for their child. Duric and colleagues4 examined the efficacy of neurofeedback for the treatment of children and adolescents with ADHD. The aim of neurofeedback is to enhance beta and depress theta activity as assessed by EEG.

The researchers randomized 130 youth with ADHD to treatment with methylphenidate, neurofeedback, or neurofeedback plus methylphenidate. The youths in the neurofeedback group had scalp sensors and were given feedback regarding their brain activity to enhance theta and depress beta activity when playing video games or watching films. There were 30 40-minute neurofeedback sesions 3 times a week.

Youths in the medication group received methylphenidate twice a day at doses of approximately 1 mg per kg daily: 91 children (70%) completed treatment. There were no significant differences in demographic factors between subjects who completed treatment and those who dropped out of treatment. The outcome measure was a clinician administered rating scale to assess attention and hyperactivity. All three treatment groups showed significant improvement in inattention and hyperactivity, with the greatest gains for reduction in hyperactivity as per parent report. There were no significant differences among the treatment groups. The authors suggest that neurofeedback be used as alternative therapy for children who do not respond to stimulant treatment.

Parents’ concerns

What factors are involved in parents’ decision to begin medication treatment for a child with ADHD? Coletti and colleagues5 conducted a focus-group study to determine factors that influenced parents’ decision. The study consisted of 27 parents of children aged 5 to 9 years with a diagnosis of ADHD. Parents were given a recommendation for stimulant treatment by a child psychiatrist. The majority of the parents (81.5%) had pursued recommended stimulant treatment.

The factor most related to parents’ decision to initiate stimulant treatment was the belief that stimulant medication was effective and that improvement of the child’s ADHD symptoms would lead to functional improvement such as better social and academic functioning. They also felt that medication might prevent more serious outcomes in the future such as juvenile delinquency. A major barrier to stimulant treatment was the parents’ concern about adverse effects such as tics and reduced appetite. Another concern was that the medication would change the child’s personality.

Some parents wanted to defer medication treatment until nonpharmacological modalities had been tried such as behavior modification or nutrition therapy. Parents had positive perceptions of psychiatrists who were collaborative, provided information about ADHD, and were empathetic. The investigators conclude that parents’ attitudes about stimulant treatment for ADHD needs to be carefully assessed at the initial evaluation in order to address the concerns and to foster adherence to sound clinical treatment recommendations.

The children’s perspectives

What are children’s views of taking stimulants for treatment of their ADHD? Singh6 examined children’s experiences with taking stimulant medication for treatment of ADHD. Children, ages 9 to 14 years, who were diagnosed with ADHD and taking stimulant medication were interviewed. They were asked whether they felt like themselves or whether the medication made them feel like a different person (which the investigator termed “a threat to authenticity”). The majority of children denied that the medication made them feel like a different person; rather they believed the medication helped them to behave better. Overall, children were positive about receiving stimulant treatment for ADHD.

This article was originally posted online on 2/3/2014.

Disclosures:

Dr Wagner is the Marie B. Gale Centennial Professor and Vice Chair in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and Director of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston.

References:

1. Klein RG, Mannuzza S, Olazagasti MAR, et al. Clinical and functional outcome of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder 33 years later. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:1295-1303.

2. Lichtenstein P, Halldner L, Zetterqvist J, et al. Medication for attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder and criminality. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2006-2014.

3. Hammerness P, Joshi G, Doyle R, et al. Do stimulants reduce the risk for cigarette smoking in youth with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder? A prospective, long-term open-label study of extended-release methylphenidate. J Pediatrics. 2013;162:22-27.

4. Duric NS, Assmus J, Gunderson D, Elgen IB. Neurofeedback for the treatment of children and adolescents with ADHD: a randomized and controlled clinical trial using parental reports. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:107.

5. Coletti DJ, Pappadopulos E, Katsiotas NJ, et al. Parent perspectives on the decision to initiate medication treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child and Adolesc Psychpharm.2012;22:226-237.

6. Singh I. Not robots: children’s perspectives on authenticity, moral agency and stimulant drug treatments. J Med Ethics.28 August 2012. http://jme.bmj.com/content/early/2012/08/27/medethics-2011-100224.full. Accessed November 5, 2013.

Newsletter

Receive trusted psychiatric news, expert analysis, and clinical insights — subscribe today to support your practice and your patients.