Publication

Article

Psychiatric Times

A Year of Record-High Suicide Rates

Author(s):

The suicide rate in the United States recently reached its highest peak since 1941.

Kurt/AdobeStock

According to new data from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the suicide rate in the United States recently reached its highest peak since 1941. The provisional number of suicides in 2022 was 3% higher than the final total number of suicides in 2021—and the 2022 final total number of suicides is likely higher than current counts.1,2 What can we learn from these statistics?

Exploring the Trends

“Is this really an out-of-the-blue story, and are we surprised by the rise? Or is this that steady rise that we have continuously seen over the years?” Fuad Khan, MD, a psychiatrist in Dover, New Hampshire, who is affiliated with multiple hospitals in the area, including Wentworth-Douglass Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital, told Psychiatric Times.

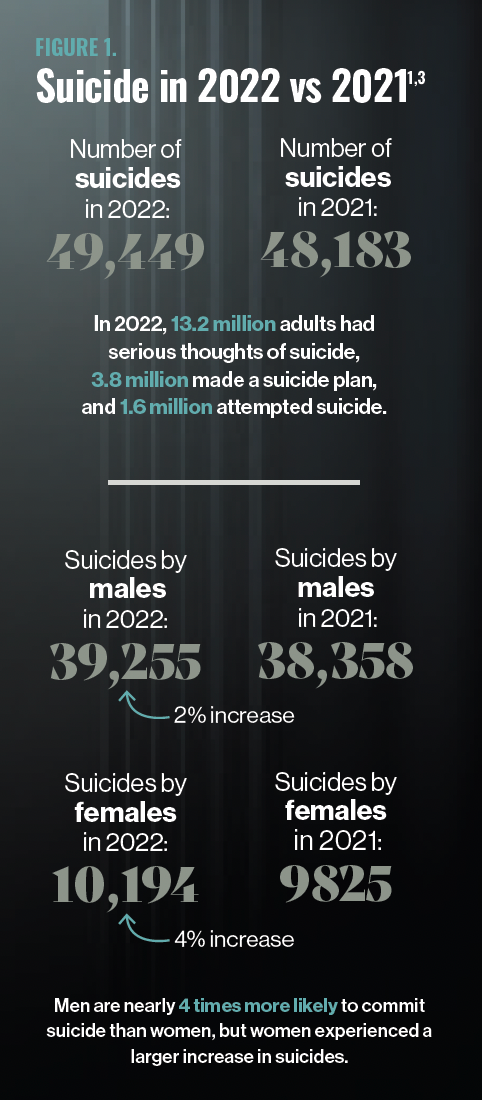

Figure 1. Suicide in 2022 vs 20211,3

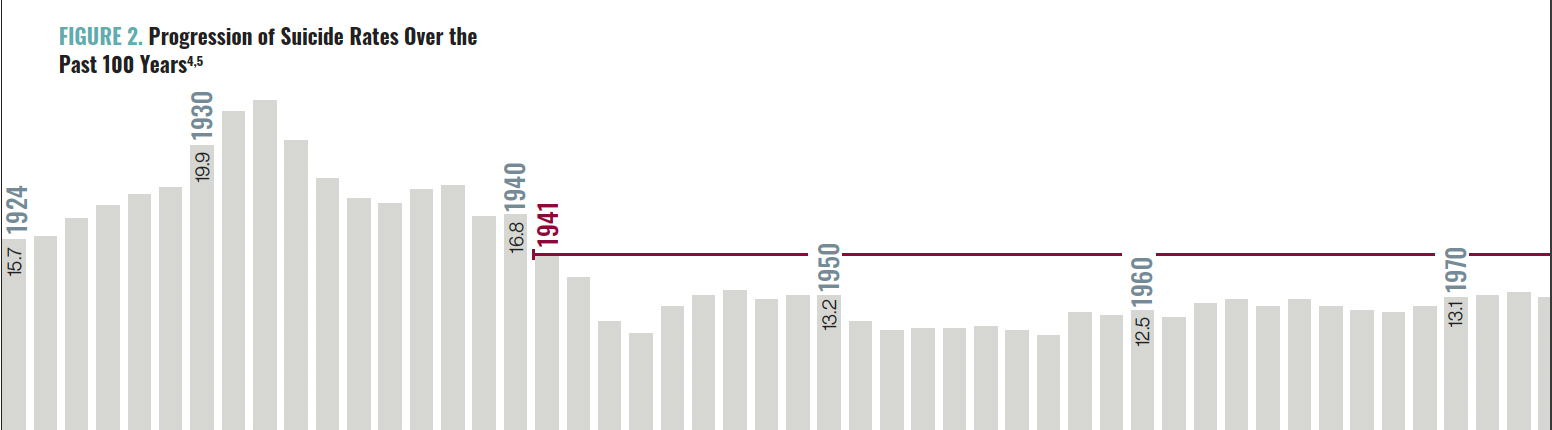

At a glance (Figure 11,3), it is easy to say the issue of suicide in the United States is worsening; however, the reason behind this troubling increase is multifactorial and complicated. Figure 2 shows the rate of suicide progression over the past 100 years, indicating a fairly steady increase since 2000, when the rate was at its lowest, at 10.4 per 100,000 individuals.4,5 The suicide rate increased in 2022 to 14.3 suicides per 100,000 individuals; although it is not quite as high as the rate in 1941 (15), it is troubling compared with the suicide rate a decade ago (2012; 12.6). The highest rate of suicide in the past 100 years was in 1931, at 21.9, during the Great Depression.5 Are we headed toward such an increased rate in the 2030s?

Figure 2. Progression of Suicide Rates Over the Past 100 Years, Part 14,5

Figure 2. Progression of Suicide Rates Over the Past 100 Years, Part 24,5

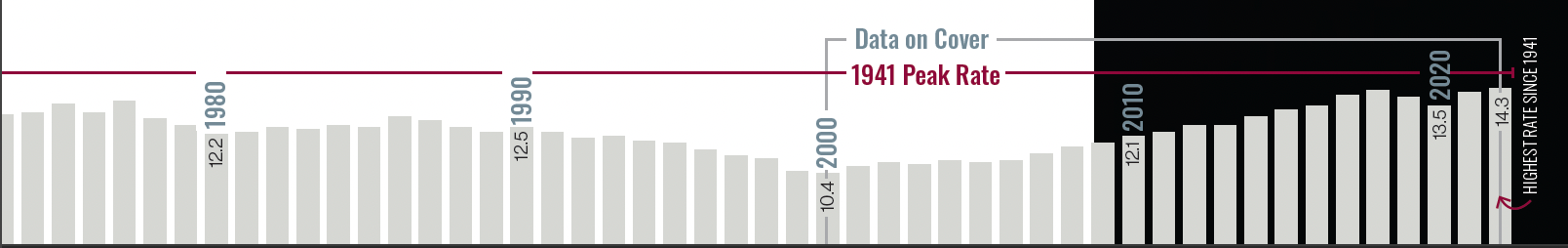

Method of suicide may play a crucial role in the current increased rate. More than 50% of suicides in the United States are completed via firearms, the most lethal of suicide methods (Figure 3).4 Approximately 90% of attempted suicides using a gun result in death; comparatively, only 13.5% of drug poisonings result in death.6 According to research, blocking access to firearms could elicit a drop of suicides. Researchers in a Connecticut study estimated that 1 suicide was averted for every 10 to 20 gun seizures between 1999 and 2013. Furthermore, 21 of the 762 recorded gun-removal cases in the study ultimately ended with the person committing suicide after they were again eligible to purchase a gun or after their guns were returned by authorities.7 A more recent follow-up to this study in Indiana found similar results, with researchers extrapolating that 1 life was saved for every 10 gun seizures.8

Figure 3. Method of Suicide4

“Firearms can be a polarizing and political issue, so it is important to not shy away from talking about it, and when you do, be nonjudgmental and frame it as a health and safety issue,” said Margie Balfour, MD, PhD, psychiatrist and chief clinical quality officer at Connections Health Solutions and an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Arizona in Tucson.

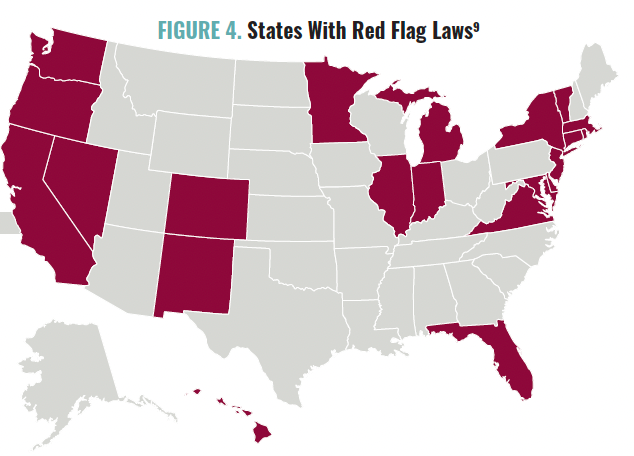

As of June 2023, 21 states had passed Extreme Risk laws, which allow authorities to remove firearms temporarily from individuals who could be considered dangerous to themselves or others (Figure 4).9 Laws like these are associated with drops in suicide; Indiana saw a 7.5% drop in gun suicides in the decade following the law’s passage, and Connecticut’s rate dropped 13.7%.10

The 2023 data will likely not be released for several months.

Understanding the Causes and Solutions

Figure 4. States With Red Flag Laws9

With an increased suicide rate, what role should psychiatry in general and clinicians specifically play in prevention? Psychiatric Times spoke with experts in the field to better understand the causes and the possible solutions for preventing suicide.

CAUSES

Trauma

“Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, we have observed increasing rates of mental health challenges, including depression, anxiety, and suicide. As a trauma practitioner, I attribute a lot of it to the accumulation of chronic stress and trauma in our population due to the pandemic as well as other traumatic events (shootings, wars, racial trauma, etc) that have been happening in the US and the world,” said Viktoriya Karakcheyeva, MD, director of behavioral health services at GW Resiliency & Well-being Center and adjunct assistant professor of clinical research and leadership at The George Washington University School of Medicine & Health Sciences in Washington, DC. “According to research, depression to a large extent is a stress- and trauma-based disorder.11 Exposure to trauma and other distressing life events accounts for approximately 50% of major depression. The most impactful life events that are linked to depression and suicide are losses, separations, and humiliations. Our population has experienced a fair share of those in various proportions and intensity, which contributed to the increasing depression and suicide rates we see right now. So it is not 2022 being a traumatic year in itself, rather an accumulation of trauma over the period of time that produced such a tragic effect.”

COVID-19

“Death by suicide is a complex phenomenon associated with a wide array of risk factors and causes that vary based on demographics. Due to the high degree of complexity, including inherent limits of data collection related to cause of death, we can only speculate about the potential reasons for the record high numbers in the US,” said Rhonda Schwindt, DNP, RN, PMHNP-BC, PMHCNS-BC, a tenured associate professor at The George Washington University School of Nursing. “One possibility is the lingering effects of the COVID epidemic. A possible connection between suicidal ideation, attempts, and death among individuals living with long COVID is currently being studied, which may shed some light on the increase of deaths by suicide in 2022. There is also a consensus among experts in the field that suicide rates often decrease during a crisis, such as an epidemic, only to climb as individuals attempt to cope with, and adjust to, the long-term effects.”

“Individuals are still feeling the effects of the increases in mental health symptoms and disruption in social relationships associated with the COVID pandemic, which affected young people particularly hard. Workforce shortages have worsened existing problems with access to mental health care, especially in rural areas,” said Balfour.

A Broken Health Care System

“Right now, we are at a point where suicide is seen as a mental health problem. It is thrown at the mental health care system—the most poorly funded and poorly supported health care specialty,” Khan told Psychiatric Times. “Suicide is a multifaceted problem that has its roots in the social structure; the way that society is trending; the narrow focus that this is only the problem of health care and especially mental health care, which is poorly funded; and the fact that the solutions for individuals in crisis go beyond what health care can provide.”

Increased Loneliness

“Social isolation and loneliness are huge risk factors for mental health issues and depression and suicide specifically. Promoting social engagement in our communities such as participation in community activities and groups can greatly increase a sense of connection, particularly in our senior male population,” said Karakcheyeva.

“The loneliness that we are facing, through and post pandemic, is strong. We will probably see more and more scientific studies of loneliness in our general population, which will be helpful eventually,” said Michael F. Myers, MD, professor of clinical psychiatry at SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University in Brooklyn, New York. “It was not that long ago that loneliness was considered a bad word. If somebody described themselves as lonely, others sort of thought, ‘Oh, they are pathetic.’ There is stigma associated with that, especially in terms of gender. At least some women talked about loneliness, but very few men would.”

SOLUTIONS

Telepsychiatry

“There is global shortage of mental health clinicians, and as a result, many people go without the help they need. We need to remove barriers to telepsychiatry, especially in underserved regions; increase funding for psychiatric/mental health training programs; and eliminate state regulations that prevent advanced-practice nurses from practicing to the full extent of their licensure,” Schwindt told Psychiatric Times.

Screening

“Most individuals who die by suicide have seen a medical or mental health professional in the 3 months leading up to their death. This means that there was an opportunity during any of those visits to ask about suicidal thoughts,” said Tia Dole, PhD, chief 988 lifeline officer of Vibrant Emotional Health in New York, New York. “The most effective screening is one that actually happens. Of course, some biases come into play. For example, clinicians do not ask people about suicidal ideation based on their presentation, appearance, or identity. We want folks to be asked, no matter who they are or how they seem.”

Myers recommends 5 screening protocols: Emergency Department Safety Assessment and Follow-up Evaluation–Patient Safety Screener, Suicide Assessment Five-Step Evaluation and Triage for Clinicians Pocket Card, Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale, Scale for Suicide Ideation, and Ask Suicide-Screening Questions Toolkit.

“Having been a decades-long clinician myself, but also a clinical researcher in this area, I think when clinicians pay attention to some of the risk factors in our populations, it heightens our own our vigilance, our screening,” added Myers.

988

“The more we can get public health messages out there, the better. The 988 number is one of the long overdue initiatives,” shared Myers. “It is simple, just 3 digits. Before, for some individuals who were desperate to call someone, a 1-800 number could be daunting. Maybe they could not even remember all the digits or did not have the strength to punch in all those numbers. Now we have to make sure there is continued funding for 988.”

Clinician Resources

Lastly, although it is important to combat the epidemic of suicides, acknowledging how a patient’s suicide affects the clinician is also critical. “You can go to a therapist. You can speak to your spouse or your friends. You need to really talk about yourself and how you are doing, not so much the specifics of the treatment. That kind of support is very, very helpful. I have certainly used it a lot through my entire career,” said Myers.

Specifically, Myers recommends several resources for clinicians who have lost a patient to suicide. The Coalition of Clinician-Survivors is a group that provides support to clinicians who have experienced a suicide loss (cliniciansurvivor.org). “Losing a Patient to Suicide: Navigating the Aftermath,” is an article in Current Psychiatry that focuses on clinician concerns following a patient suicide.12 Collateral Damages: The Impact of Patient Suicide on the Physician is an educational film that shows several clinicians speaking about their experience of losing a patient to suicide.13

References

1. Curtin SC, Garnett MF, Ahmad FB. Provisional Estimates of Suicide by Demographic Characteristics: United States, 2022. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System; November 2023. Accessed March 5, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsrr/vsrr034.pdf

2. McPhillips D. Suicide deaths reached a record high in the US in 2022, despite hopeful decreases among children and young adults. CNN. November 29, 2023. Accessed March 5, 2024. https://www.cnn.com/2023/11/29/health/suicide-record-high-2022-cdc/index.html

3. Highlights for the 2022 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Accessed March 5, 2024. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt42731/2022-nsduh-main-highlights.pdf

4. Suicide data and statistics. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. November 29, 2023. Accessed March 5, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/suicide-data-statistics.html

5. Historical data, 1900-1998. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. Accessed March 5, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/mortality_historical_data.htm

6. Conner A, Azrael D, Miller M. Suicide case-fatality rates in the United States, 2007 to 2014: a nationwide population-based study. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(12):885-895.

7. Swanson J, Norko M, Lin HJ, et al. Implementation and effectiveness of Connecticut’s risk-based gun removal law: does it prevent suicides? Law Contemp Prob. 2017;80:180-208.

8. Swanson JW, Easter MM, Alanis-Hisrich K, et al. Criminal justice and suicide outcomes with Indiana’s risk-based gun seizure law. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2019;47(2):188-197.

9. Everytown Research & Policy. Which states have Extreme Risk laws? Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund. Updated January 4, 2024. Accessed March 5, 2024. https://everytownresearch.org/rankings/law/extreme-risk-law/

10. Kivisto AJ, Phalen PL. Effects of risk-based firearm seizure laws in Connecticut and Indiana on suicide rates, 1981–2015. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(8):855-862.

11. Kendler KS, Hettema JM, Butera F, et al. Life event dimensions of loss, humiliation, entrapment, and danger in the prediction of onsets of major depression and generalized anxiety. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(8):789-796.

12. Gutin NJ. Losing a patient to suicide: navigating the aftermath. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(11):17-24.

13. Prabhakar D, Anzia JM, Balon R, et al. “Collateral damages”: preparing residents for coping with patient suicide. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(6):429-430.

Newsletter

Receive trusted psychiatric news, expert analysis, and clinical insights — subscribe today to support your practice and your patients.