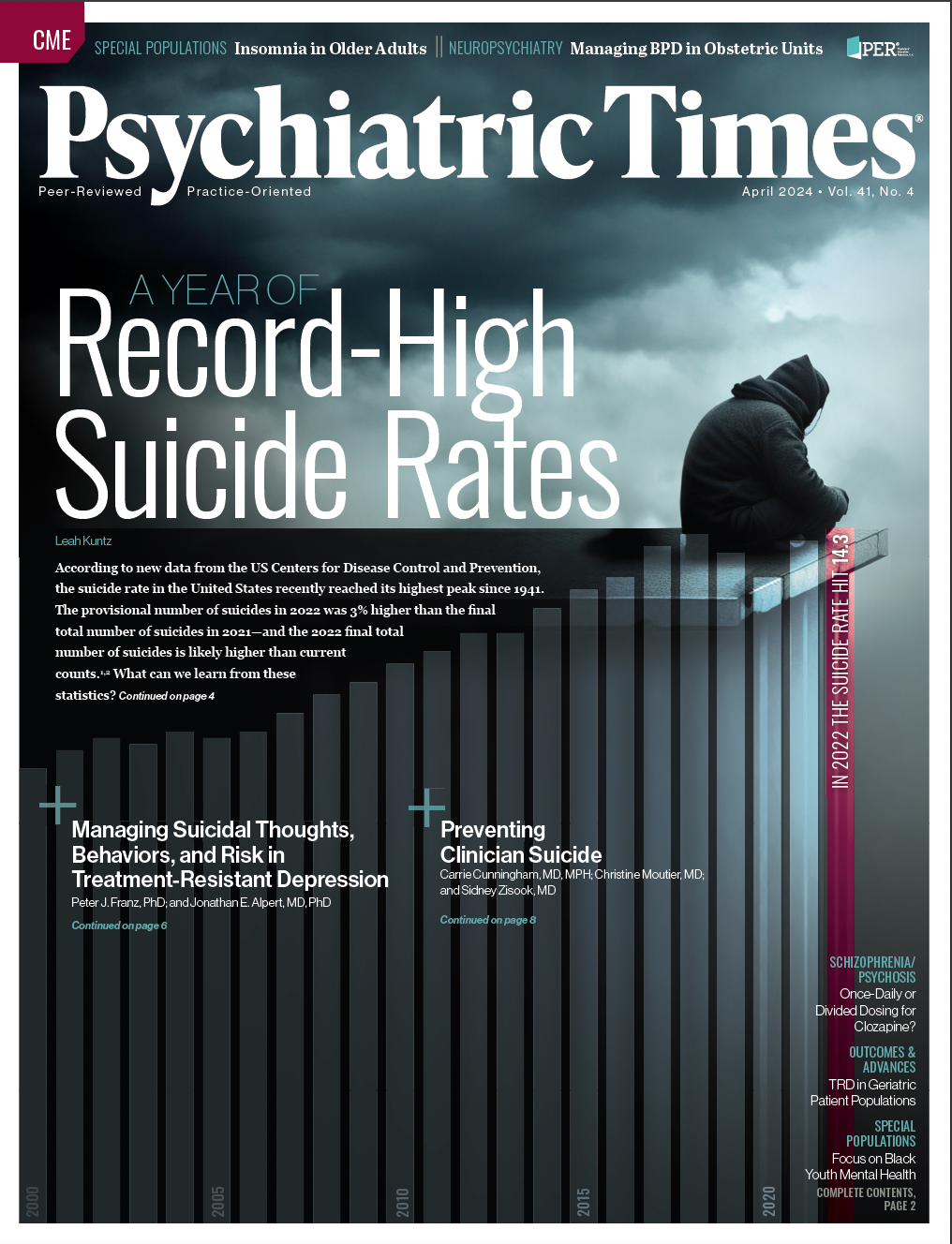

Publication

Article

Psychiatric Times

Preventing Clinician Suicide

Author(s):

Although the practice of medicine can be immensely rewarding, it also can be extraordinarily stressful. Here's how we can help prevent clinician suicide.

vectorfusionart/AdobeStock

In February 2023, I gave my presidential address for the Association for Academic Surgery.1 I did something scary. I told the truth.

I began my speech like this: “Yes, I was the top junior tennis player in the nation, won the Junior US Open, and was ranked top 50 in the world professionally at the age of 16. I have competed at Wimbledon 5 times. I am an associate professor of surgery at Harvard. I have an NIH [National Institutes of Health] grant. I am the president of the Association for Academic Surgery. I am also human.”

Although I looked great on paper, I was just like anybody else. I am human. I spoke about my lifelong struggle with depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, substance use, and a yearlong mental health crisis.

Asking for help was not in my armamentarium. I am pathologically driven and stubborn. I had built an internal fortress over a lifetime. I would not have stepped away from work unless forced to. That was only the beginning, though. The journey away from work, through scary back alleys, and back to that stage. Calls with the Employment Assistance Program, referral to the physician health program, evaluation (and failing an evaluation) of fitness, 3 months in intensive inpatient and outpatient treatment, and continuing monitoring and recovery work. None of my professional successes have protected me against this.

It was bumpy, ugly, and terrifying. It still is sometimes. I felt humiliated, broken, and at times hopeless. It was the hardest thing I have ever done—and am still doing.

The speech, even before it was posted online, resulted in an outpouring of responses. Many shared their stories or asked permission to screen my talk for their departments. Thousands have viewed the YouTube video; millions read a related article in The Guardian.2 This is only to illustrate how much others need to hear it. That someone else felt the things they feel. The timing was right. It resonated. It resounded.

My story is not unique. I am not an exception. Although my journey was arduous, it was worth it. I am privileged and grateful to have the resources to support my recovery. But things with meaning do not come easily. I am peaceful and hopeful. By working on myself, I know I am a better doctor, mother, friend, and self.

—Carrie Cunningham, MD, MPH

Scope of Clinician Suicide

As Dr Cunningham’s story so well illustrates, none of us are immune to the mental health struggles faced by all humankind. Although the practice of medicine can be immensely rewarding, it also can be extraordinarily stressful. Life-or-death decisions are made daily, and physicians are asked to care for patients in what is often the most challenging phase of their and their families’ lives.3 Many of us are wired toward perfectionism and an unrealistic sense of what it means to wear the mantle of our professions. Mental health needs are ubiquitous and simply part of being human. Thus, it is not surprising that physicians and other health care workers experience high rates of imposter syndrome, acute stress reactions, burnout, dissatisfaction with life and career, depression, substance use, and suicide.4 Most post–COVID-19 surveys show burnout rates of 50% and higher for doctors, nurses, and other health care workers,3-6 rates of depression at least as high as in workers not in health care, and recent or current suicidal ideation hovering around 10%. Suicide remains the leading cause of death among male physician residents7 and is more common among female physicians than female nonphysicians8 as well as among both male and female nurses than their gender-matched nonnurse counterparts.9

Avoiding Care

As she says, Dr Cunningham’s story is far from unique. Mental health disorders are common in health professionals. In her presidential address, she stated: “Few seek help, and those that do write their own prescriptions, pay cash for medication, go to other cities for treatment for fear of being found out.”2 Her story illustrates many of the roadblocks preventing physicians and other health care workers from accessing mental health care: perfectionistic striving, fear of negative repercussions, moral injury, cumulative occupational trauma, and the tenet of “patients above all else.”

These tenets leave little room for the inevitable challenges and perceived loss of control that come with being human. Although perfectionism undoubtedly leads to external successes, it also prevents you from seeking help, from admitting to yourself or anyone else that you are human. It isolates you. If perfection is your goal, you will live your life in a constant state of perceived or feared failure.

Additional roadblocks Dr Cunningham exemplified center around the theme of stigma: licensing, accreditation, promotion and employability concerns, and potential loss of reputation if she sought treatment. Added to these are difficulties with scheduling and convenience, perceived lack of confidentiality, documentation in electronic medical records, cost, perceiving problems as not important enough to warrant treatment, and lack of conviction in the effectiveness of mental health care.10 Identity with the profession is so engrained, interwoven, and lauded that it makes seeking help seem like a moral failing. Thus, despite their knowledge and resources, physicians are no more likely than others to seek mental health care.11 The consequences are significant. Unattended burnout and depression lead not only to unhappiness and despair but also work dissatisfaction, career attrition, medical errors, and home life disruption.12 Most critically, untreated depression may be the most actionable risk factor for physician suicide.13

For all these reasons, barriers to care can and must be overcome. The good news is that stigma is lessening; the more we talk about mental health and suicide, the more inroads will be made. Physicians like Dr Cunningham telling their stories is a major step forward. The Dr Lorna Breen Heroes Foundation, formed by Dr Breen’s family to honor her life and memory, has made major progress in advocating for health care provider mental health and humanizing state licensing procedures for doctors and nurses.14 Prioritizing physician and caregiver self-care and well-being is championed by major medical and nursing organizations,15 and the World Medical Association has added the professional responsibility “I will attend to my own health, well-being, and abilities in order to provide care of the highest standard” to the Declaration of Geneva.16

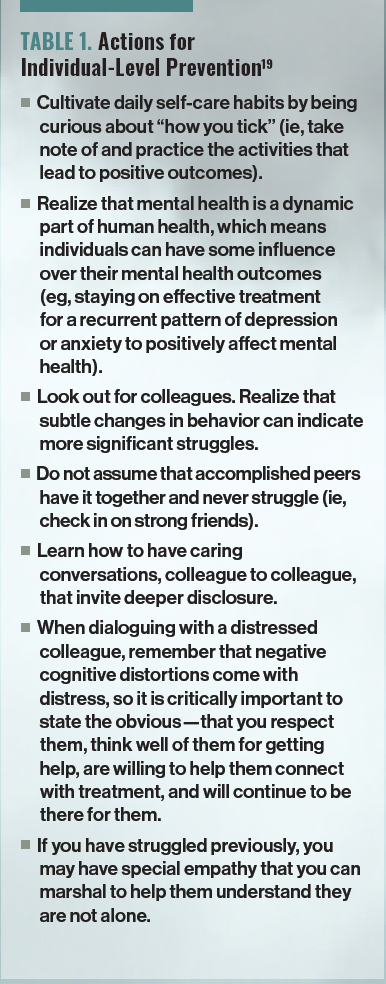

Table 1. Actions for Individual-Level Prevention19

Updating the Culture

The outworn medical culture of subverting personal and family priorities for patient needs, stoicism, self-sufficiency, and never asking for help is slowly being updated to make room for a culture of wellness that also prioritizes time with family, friends, and loved ones; adequate sleep, nutrition, hydration, and exercise; accepting humanness and imperfection; staying connected; asking for help; and sharing control.17 Upgrading the culture in this way does not eliminate outstanding patient care but rather allows clinicians to provide the kind of compassionate and skillful care their patients deserve.

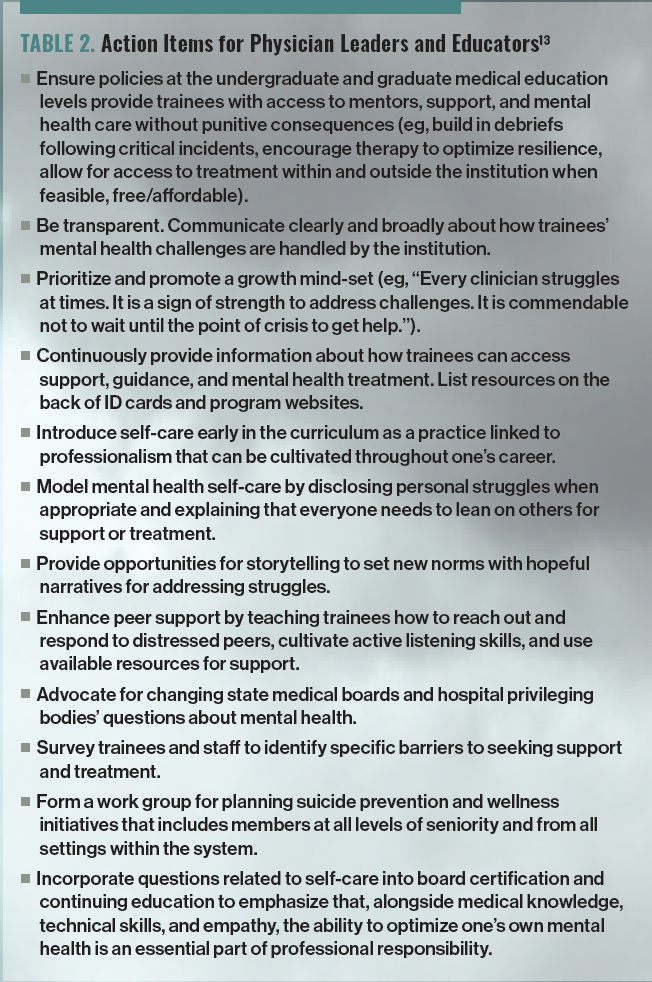

Table 2. Action Items for Physician Leaders and Educators13

Evidence-Based Suicide Prevention Strategies

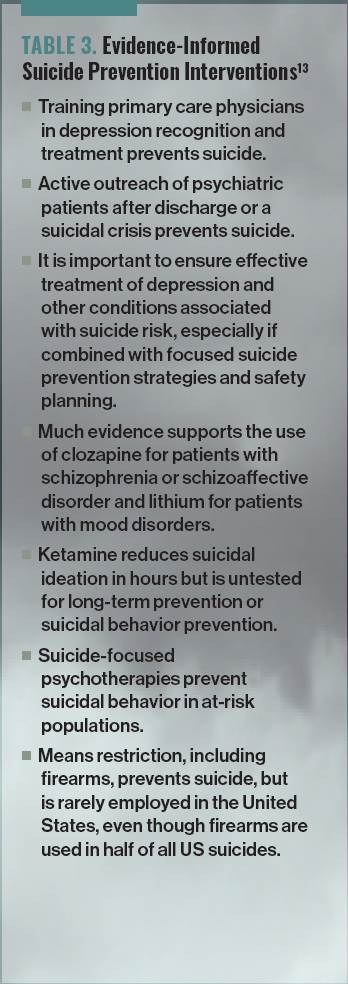

Since suicide is a complex health outcome with many drivers of risk, effective strategies require strategic, multipronged, longitudinal, evidence-based actions.18 Reducing the risk of clinician suicide requires individual- and system-level steps such as addressing regulatory policies, making changes in curricula and role modeling in medical education, increasing access to affordable mental health care, and transforming an entrenched culture. Table 1 provides several examples of individual-level actions for clinician suicide prevention.19 Table 2 provides examples of physician leader- and educator-level actions. In addition, clinicians are susceptible to and helped by the same evidence-based treatments that are applicable to patients in the general community.13 Table 3 lists some of the best studied suicide prevention strategies applicable to all.13

Table 3. Evidence-Informed Suicide Prevention Interventions13

Screening, Engaging, and Facilitating Support

Positive changes are happening at many organizations and institutions. At UC San Diego Health, the Healer Education Assessment and Referral (HEAR) program offers a voluntary and anonymous online screening, engagement, and referral tool that includes a stress and depression screening questionnaire from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention’s web-based Interactive Screening Program (ISP).20,21 HEAR supplements the ISP with a robust education program meant to inform about health care worker burnout, depression, and suicide; address stigma; and break down barriers to care. Since its inception in 2009, several additional support programs, like short-term free and anonymous therapy for house staff, individual check-ins with HEAR counselors for training programs and clinical units upon request, group debriefs after critical incidents and other potentially traumatic situations, peer support trainings, and Schwartz Rounds, have been added.22 More than 1000 mental health referrals have been made. Several other medical- and professional-degree schools, hospitals, health systems, and organizations have implemented the ISP and components of HEAR in their own institutions and disciplines,23,24 and the program has received national acknowledgement.4

Concluding Thoughts

It takes a village. Preventing clinical suicide requires a multifaceted approach including development of interpersonal coping mechanisms, provisions of affordable mental health resources, legislative protection of privacy for credentialling and licensure, and lessening of stigma through storytelling and normalization. We can effect change. There is hope.

Dr Cunningham is associate professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts. Dr Moutier is chief medical officer at the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

Dr Zisook is a distinguished professor of psychiatry at UC San Diego in California.

References

1. 2023 Association for Academic Surgery Presidential Address: Removing the Mask. Academic Surgical Congress YouTube page. Accessed December 20, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JaNBH4UPHv4

2. Frangou C. US surgeons are killing themselves at an alarming rate. One decided to speak out. The Guardian. September 26, 2023. Accessed December 20, 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2023/sep/26/surgeons-suicide-doctors-physicians-mental-health

3. Murthy VH. Confronting health worker burnout and well-being. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(7):577-579.

4. Addressing Health Worker Burnout: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on Building a Thriving Health Workforce. Office of the Surgeon General; 2022.

5. Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sinsky C, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2017. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(9):1681-1694.

6. Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD, Johnson PO, et al. A cross-sectional study exploring the relationship between burnout, absenteeism, and job performance among American nurses. BMC Nurs. 2019;18:57.

7. Yaghmour NA, Brigham TP, Richter T, et al. Causes of death of residents in ACGME-accredited programs 2000 through 2014: implications for the learning environment. Acad Med. 2017;92(7):976-983.

8. Ye GY, Davidson JE, Kim K, Zisook S. Physician death by suicide in the United States: 2012–2016. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;134:158-165.

9. Davidson JE, Proudfoot J, Lee K, et al. A longitudinal analysis of nurse suicide in the United States (2005–2016) with recommendations for action. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2020;17(1):6-15.

10. Mihailescu M, Neiterman E. A scoping review of the literature on the current mental health status of physicians and physicians-in-training in North America. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1363.

11. Gold KJ, Andrew LB, Goldman EB, Schwenk TL. “I would never want to have a mental health diagnosis on my record”: a survey of female physicians on mental health diagnosis, treatment, and reporting. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;43:51-57.

12. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283(6):516-529.

13. Mann JJ, Michel CA, Auerbach RP. Improving suicide prevention through evidence-based strategies: a systematic review. Am J Psychiatry. 2021;178(7):611-624.

14. Sacopulos MJ, Feist JC. The Dr. Lorna Breen Heroes’ Foundation and Physician Suicide Awareness. American Association for Physician Leadership. October 8, 2022. Accessed December 20, 2023. https://www.physicianleaders.org/articles/dr-lorna-breen-heroes-foundation-physician-suicide-awareness

15. Moutier CY, Myers MF, Feist JB, et al. Preventing clinician suicide: a call to action during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Acad Med. 2021;96(5):624-628.

16. Parsa-Parsi RW. The revised declaration of Geneva: a modern-day physician’s pledge. JAMA. 2017;318(20):1971-1972.

17. Menon NK, Trockel M. Creating a culture of wellness. In: Roberts LW, Trockel M, eds. The Art and Science of Physician Wellbeing: A Handbook for Physicians and Trainees. Springer; 2019:19-32.

18. Melhem N, Moutier CY, Brent DA. Implementing evidence-based suicide prevention strategies for greatest impact. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ). 2023;21(2):117-128.

19. Moutier C. Physician mental health: an evidence-based approach to change. J Med Regul. 2018;104(2):7-13.

20. Moutier C, Norcross W, Jong P, et al. The suicide prevention and depression awareness program at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine. Acad Med. 2012;87(3):320-326.

21. Mortali M, Moutier C. Facilitating help-seeking behavior among medical trainees and physicians using the interactive screening program. J Med Regul. 2018;104(2):27-36.

22. Norcross WA, Moutier C, Tiamson-Kassab M, et al. Update on the UC San Diego healer education assessment and referral (HEAR) program. J Med Regul. 2018;104(2):17-26.

23. Haskins J, Carson JG, Chang CH, et al. The suicide prevention, depression awareness, and clinical engagement program for faculty and residents at the University of California, Davis Health System. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40(1):23-29.

24. ISP for medical schools, hospitals and health systems. American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. Accessed December 20, 2023. https://afsp.org/isp-for-medical-schools-hospitals-and-health-systems/

Newsletter

Receive trusted psychiatric news, expert analysis, and clinical insights — subscribe today to support your practice and your patients.