Publication

Article

Psychiatric Times

Speaking Up: Sexual Harassment in the Medical Setting

Author(s):

Here: a review of the definition of sexual harassment, its prevalence among physicians and medical students, its potential impact on physicians and trainees, and guidance about its management.

FIGURE 1.

FIGURE 2.

This article will briefly review the definition of sexual harassment, its prevalence among physicians and medical students, and its potential impact on physicians and trainees. It will also provide some guidance about its management.

Public awareness about the topic has increased since the 1990s when Attorney Anita Hill made allegations of sexual harassment about Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas. The authors became interested in this topic after a third-year medical student approached her Clerkship Coordinator to report she was confused about what to do because a male patient had brushed his hand on her backside on the inpatient psychiatric unit. When she reported the incident to her female supervisor, she was told, “Don’t make a big deal about it, it happens.”

Definition

For purposes of this article, we use the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) definition of sexual harassment. In 1980, the EEOC defined sexual harassment as unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature.1

Prevalence of sexual harassment

The US Merit Systems Protection Board conducted surveys in 1980, 1987, and 1994, and each of the surveys yielded similar results.2 In the first survey, 42% of women and 15% of men reported sexual harassment on the job; in the second survey, the same percentage of women and 14% of men reported sexual harassment; and in the third survey, 44% of women and 19% of men reported sexual harassment.

Sexual harassment appears to be common during medical training. A meta-analysis of data on the topic reported that 59.4% of medical trainees, including medical students, interns, and residents in all specialties, had experienced some form of harassment.3 Another study of emergency medicine residents found that 68.9% of women and 41.9% of men responders reported sexual harassment.4

A 1994 survey of interns and residents in an internal medicine residency program showed that a total of 83 episodes of sexual harassment had occurred.5 Of these, 41 occurred during medical school and 42 during residency. About 77% of women did not report the harassment because they were not confident it would help, and 82% of men felt they could deal with the problem with no outside help. Women also reported fear of retaliation and feelings of shame and guilt. Other reasons were fear of not being believed, embarrassment, lack of trust in authority figures, and lack of familiarity with available resources.

A New Zealand study in 2001 that included trainees from all specialties showed that 20% of them had been sexually harassed: women were more likely to report the harassment than men were.6 Most harassers of women in hospitals tend to be male-whether attending physicians or others-and most episodes are likely to happen during medical school. Harassers of men were reported to be mostly nurses; these incidents tended to occur during residency and were found to be mostly non-physical in nature.5

A British survey of 100 male and female psychiatric trainees showed that 86% reported unwanted sexual contacts such as deliberate touching, leaning over or cornering, letters, telephone calls, and exposure to sexual material. Most of the offenses were perpetrated by patients.7

Findings indicate that female doctors are mostly harassed in their offices by their patients, but also in high-risk areas such as inpatient wards or walk-in clinics.6 Harassment also occurs in emergency departments, where there is a large proportion of previously unknown patients, as well as patients under the influence of alcohol or drugs.

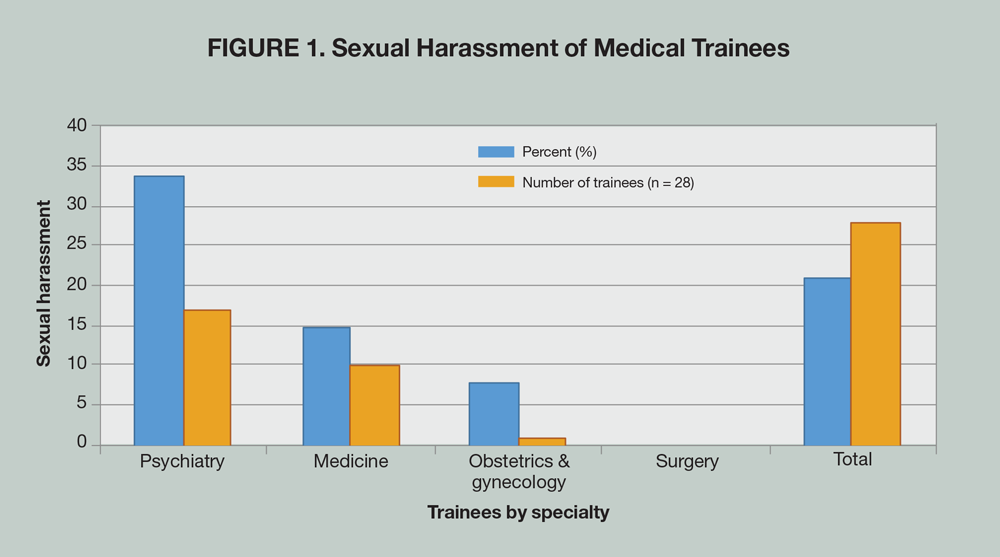

In the New Zealand study, more than half of all trainees reported some form of threat by patients, and one-fifth had been sexually harassed. Psychiatric trainees were identified as being more at risk than other trainees in medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, and surgery (Figure 1).

Harassment is not limited to medical trainees. A 1995 cross-sectional survey showed that 52% of women compared with 5% of men on US academic medical faculties reported having been harassed.8 The hospital environment might foster such behaviors because doctors and trainees spend long hours working in a very stressful environment, doing physical examinations as well as discussing contraception, marital infidelities, sexual abuse, and other “sexual” topics.5

A 2014 study that looked at both sexual harassment and gender discrimination among academic medicine faculty showed that 30% of women and 4% of men reported sexual harassment; 47% of the women noted that these experiences negatively affected their professional advancement, although no specifics were provided.9 In the same study, 66% of women and 56% of men reported experiencing gender bias in professional advancement.

Sexual harassment in psychiatry

Morgan and Porter7 found a higher prevalence of sexual harassment in psychiatric practices than in primary family medicine practices. Many incidents were reported but dismissed as “part of the job.” In addition, when harassers were patients, their psychiatric diagnoses often altered the perception of their behavior. For example, delirium and psychoses were protective of accusations of sexual harassment. Other diagnoses such as dementia, mania, schizophrenia, depression, substance use disorders, and personality disorders were also perceived as protective of patients, even when they exhibited unwanted sexual behaviors. These findings suggest that psychiatrists may be at an increased risk for violence and sexual victimization by psychiatric patients.

Types of sexual harassment

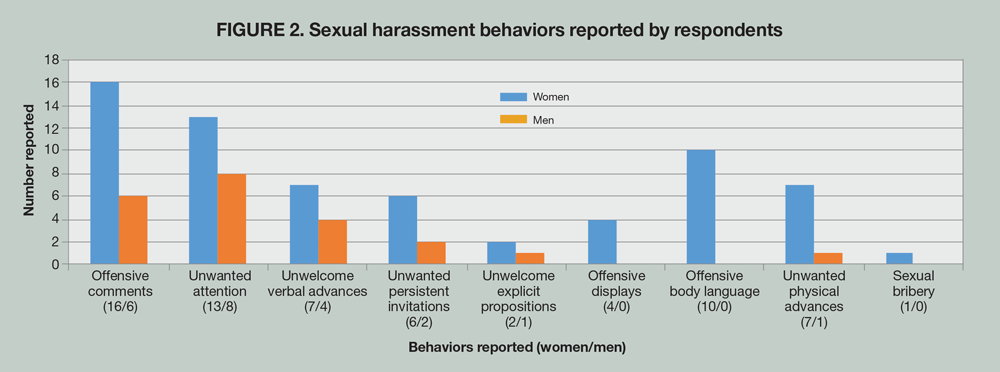

A survey of medical residents revealed types of sexual harassment: sexual remarks, offensive comments about one’s body, unwanted sexual attention and flirtation, verbal advances or inquiries, offensive displays of sexual videos/pictures, repeated leering, standing too close, rubbing, fondling, brushing, pinching, patting, threats of punishment for refusal of sexual favors or offering better grades or promotion in return for sexual favors and, finally, attempted rape and rape. Figure 2 compares sexual harassment behaviors reported by men and women using data from a survey conducted by Komaromy and colleagues5 among internal medicine trainees.

Harassment by patients of female doctors often includes suggestive looks and gestures, sexual remarks, inappropriate gifts and phone calls, exposure of body parts, inappropriate touching and requests for unwarranted physical examinations, attempted rape, and rape. Male doctors also are not exempt from harassment by patients, although it is less common.

Impact of sexual harassment on victims

The sequelae associated with sexual harassment are psychological, somatic, and work-related. Psychological effects include isolation, depression, guilt, anger, fear, low self-esteem, and helplessness. Somatic complaints are disrupted sleep, nightmares, headaches, fatigue, poor appetite, gastrointestinal disturbances, and weight loss. Work-related consequences include absenteeism, poor work evaluation, and poor work performance. An increased likelihood of depression, drug use, or suicidal thoughts has been reported as a consequence of being harassed or belittled by superiors.10

Common psychiatric diagnoses associated with victims of sexual harassment include adjustment disorder; major depression; and anxiety disorders, such as panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and PTSD. The estimated percentage of victims who suffer emotional distress as a result of these offending behaviors is as high as 90%.2 However, there is no single diagnosis associated per se with sexual harassment; additional studies are needed to address the relationship between the severity of the aggression and the psychological impact on victims.

Given the prevalence of sexual harassment in the medical field, a clinician may seek treatment from a psychiatrist for the above-mentioned conditions. The psychiatrist may also have to treat a harasser as a patient and might be asked to serve as an expert witness in a court of law. Because of bias, the psychiatrist is precluded from treating and testifying in a case of the same patient. Furthermore, the dual role of the psychiatrist may ruin the patient-doctor relationship and even worsen the patient’s condition. Therefore, an understanding of the legal issues related to sexual harassment is important.

Legal aspects of sexual harassment

There are 2 forms of sexual harassment11:

1. A “quid pro quo” when the employer enters into a relationship with the employee to obtain or retain employment, which is considered sexual bribery.

2. When the employer creates a hostile, intimidating environment for the employee.

Of course, simple words can also be misinterpreted, and a man’s perspective for judging a hostile environment may be different than a woman’s. This was notable in a 1991 California court ruling that “the appropriate perspective for judging a hostile environment claim” (when a woman is a victim) is that of “a reasonable woman.” Words can often be taken out of context: telling a woman “you look attractive today” can be meant as a compliment and taken as such, while saying to a woman “this skirt shows your great legs, wear it more often” can be seen differently.

Recommendations and management of sexual harassment

Litigation is frequently not the answer to harassment-it can lead to resentment, shame, and defensiveness. The main goal in dealing with sexual harassment is prevention and education. The following are some recommendations when interacting with patients:

• In an office setting, consider installing a reliable alarm system

• As much as possible, avoid booking new patients at the end of the day because his or her history of previous violence is unknown until evaluated

• Avoid performing physical examinations on your own

• Inpatient psychiatric wards should be equipped with security systems, panic buttons, and other warning systems in appropriate locations such as interview and treatment rooms

• High-risk patients and those with repetitive disruptive behaviors should be readily identified by incident report analysis

• Work in teams as much as possible

Training programs should take into account the long-term psychological consequences of sexual harassment and ensure that rapid responses are available. Hospital staff and medical trainees need to be educated about sexual harassment. Moreover, institution of a zero-tolerance policy and elimination of the code of silence are highly recommended. It is crucial that easy methods are used to help victims file grievances, keep complaints confidential, and appoint neutral individuals to investigate complaints.12 When harassment has occurred, employers need to take immediate and appropriate action. An unbiased approach will not only demonstrate a commitment to establishing a comfortable working and training environment, but it will also help reinforce the importance of the issue and prevent further harassment.

Conclusion

All medical professionals should learn to recognize sexual harassment behavior and not tolerate it. Victims need to quickly respond to the harasser rather than standing by meekly or stoically. If the harassment persists, it is recommended that the victim compile a written report of the occurrences. Trainees should not feel ashamed or guilty, nor feel compelled to leave their training. Such attitudes may have a serious impact not only on their education but also prevent them from reaching further professional goals.

Harassment of trainees should be reported to general medical education Deans, Chairs of departments, and residency training and clerkship Directors. Volunteer peer crisis intervention, debriefing, counseling, or psychotherapy should be made available to victims. Procedures for both investigations and disciplinary actions should be prioritized when necessary.

Acknowledgment-The authors express their gratitude to Jacques Vital-Herne, MD, for his contribution to this article. The authors acknowledge the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine (APM) for helping to bring this article to fruition. The APM is the professional home for psychiatrists providing collaborative care bridging physical and mental health. Over 1200 members offer psychiatric treatment in general medical hospitals, primary care, and outpatient medical settings for patients with comorbid medical conditions.

Disclosures:

Dr. St. Victor is Board Certified in Psychiatry and Psychosomatic Medicine, a Fellow of the American Psychiatric Association, and a Fellow of the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine. She works as the Assistant Clinical Director of Psychosomatic Medicine and the Clerkship Director for Medical Students at the Nassau University Medical Center, East Meadow, NY. Dr. Wichman is Associate Professor of Psychiatry and Obstetrics and Gynecology; Director of Women’s Mental Health, Director of the Inpatient Psychiatry Consultation Service at Froedtert Hospital; and Program Director of Psychosomatic Medicine Fellowship at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, WI. Ms. Malakkla is currently a third-year medical student at the American University of the Caribbean, doing her clerkship at Nassau University Medical Center, East Meadow, NY.

Dr. St. Victor and Dr. Wichman report no conflicts of interest concerning the subject matter of this article.

References:

1. Phillips SP, Schneider MS. Sexual harassment of female doctors by patients. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1936-1939.

2. Jorgenson LM. Workplace sexual harassment: incidence, legal analysis, and the role of the psychiatrist. Harvard Rev Psychiatry. 2000;8:94-98.

3. Fnais N, Soobiah C, Chen MH, et al. Harassment and discrimination in medical training. Acad Med. 2014;8:817-827.

4. Schnapp B, Slovis B, Shah A, et al. Workplace violence and harassment against emergency medicine residents. West J Emerg Med. 2016;17:567-573.

5. Komaromy M, Bindman AB, Haber RJ, et al. Sexual harassment in medical training. N Engl J Med. 1993; 328:322-326.

6. Coverdale J, Gale C, Weeks S, et al. A survey of threats and violent acts by patients against training physicians. Med Ed. 2001;5:154-159.

7. Morgan JF, Porter S. Sexual harassment of psychiatric trainees: experiences and attitudes. Postgrad Med J. 1999;75:410-413.

8. Carr PL. Faculty perceptions of gender discrimination and sexual harassment in academic medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:889-896.

9. Jagsi R, Griffith KA, Jones R, et al. Sexual harassment and discrimination experiences of academic medical faculty. JAMA. 2016;315:2120-2121.

10. Miedema B, Easley J, Fortin P, et al. Disrespect, harassment, and abuse: all in a day’s work for family physicians. Can Fam Phys. 2009;55:279-285.

11. Kinard JL, Mclaurin JR, Little B. Sexual harassment in the hospital industry: an empirical inquiry. Health Care Manage Rev. 1995;20:47-53.

12. Gardner S, Johnson PR. Sexual harassment in healthcare: strategies for employers. Hosp Topics. 2001;79:5-11.

Newsletter

Receive trusted psychiatric news, expert analysis, and clinical insights — subscribe today to support your practice and your patients.