The Art of Sharing DSM

In his recent blog posting, Dr Steven Moffic proposed that only psychiatrists be allowed to certify DSM diagnoses. While I disagree, I commend Dr Moffic for raising this controversial topic, which inevitably brings up a number of basic issues challenging our profession.

“This diagnostic manual is derived mainly from the expertise of psychiatrists. Given the importance of general medical knowledge in making an accurate psychiatric diagnosis, the appropriate use of this manual is for psychiatrists to certify the official diagnosis. The exception would be those who are specially trained and supervised by the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology.”

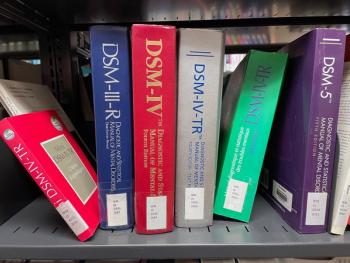

It is certainly true that DSM was derived mainly from the expertise of psychiatrists, in the sense that is a product of the

Each DSM diagnosis is primarily a list of behaviors and psychological symptoms, none of which require medical training to recognize. In fact, with a few exceptions, such as alcohol withdrawal, there are no DSM disorders listing either lab tests or physical exam findings as criteria for the diagnosis. Therefore, for the vast majority of the 300-plus diagnoses included in DSM, medical school training is not needed.

One might argue, however, that users of DSM require medical training in order to rule out a medical condition that may be secretly mimicking an apparent psychiatric disorder. But when psychologists and social workers make a psychiatric diagnosis, they generally ask patients if they have seen their primary care doctor to rule out an organic cause. I do not believe that medical school is required to train therapists to ask this question, nor to ask about certain common symptoms that are red flags for medical illness.

Furthermore, we psychiatrists are hardly immune from missing occult medical issues. Our practices tend to be much busier than those of therapists, and many psychiatrists do brief 30- to 45-minute evaluations and spend 15 to 20 minutes with patients for psychopharm follow-up visits. In such settings, it is likely that medical issues (not to mention psychosocial issues) are missed regularly. Whether we, in fact, do a better job of “catching” hidden medical problems than our therapist colleagues is an empirical question, and I am not aware of any research that has attempted to answer this question.

At any rate, it is indisputable that the core diagnostic work in psychiatry is psychological, and is not medical. During a DSM diagnostic interview, I might spend 5% of my time-if that-calling upon my medical school knowledge to rule out a medical problem. The other 95% of my time is spent obtaining a social and psychiatric history, and doing a detailed mental status exam. This work does not require stethoscopes, blood tests, or PET scans. It requires mind-to-mind contact with my patient-again, something that psychologists and social workers are quite skilled at.

I do wholeheartedly agree with

In an editorial recently published in Archives of General Psychiatry,1 Dr Thomas Insel, who is the chief of NIMH, characterized the current state of psychiatric knowledge this way: “Despite high expectations, neither genomics nor imaging has yet impacted the diagnosis or treatment of the 45 million Americans with serious or moderate mental illness each year.” He added: “While we have seen profound progress in research…the gap between the surge in basic biological knowledge and the state of mental health care in this country has not narrowed and may be getting wider.”

Someday, I have no doubt that we will understand the neurobiology of the disorders we treat, and we would then be on solid ground requiring medical school for the diagnostic process. Until then, I suggest that we resist the temptation to turn DSM into another front in the larger turf war some of us are waging in order to protect our profession.

References:

Reference

1. Insel TR. Translating scientific opportunity into public health impact: a strategic plan for research on mental illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:128-133.

Newsletter

Receive trusted psychiatric news, expert analysis, and clinical insights — subscribe today to support your practice and your patients.