The author offers a brief commentary in response to feedback from readers of a previously published case.

Dr Geppert is a professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Internal Medicine and director of ethics education at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine in Albuquerque. She is senior ethicist, Veterans Administration National Center for Ethics in Health Care, and an adjunct professor of bioethics at the Alden March Bioethics Institute of Albany Medical College. She serves as the ethics editor for Psychiatric Times.

The author offers a brief commentary in response to feedback from readers of a previously published case.

Special Reports have long been a mainstay feature of the monthly Psychiatric Times issues, but this two-part report on cultural competence and diversity is unique in both style and content.

Take the ethics quiz about a cognitively intact, highly intelligent patient with good ego strength and coping skills who plans to commit suicide.

Severe alcohol dependence and frequent relapses in this patient prompts his son to produce a durable power of attorney for health care. He demands that the physicians declare his father to lack decision-making capacity. More in this ethics case report.

The universe of psychiatric ethics has dramatically expanded. Let us boldly go together where psychiatric ethics has never gone before!

How often are you confronted with an ethical dilemma in your clinical practice? How comfortable-and how prepared-are you to deal with these issues? Those are just a few of the questions posed in the Psychiatric Times Ethics Survey-a survey that turned out to be the largest ever of its kind.

Educated and successful individuals, Mr H's children seem able to understand that their father can no longer make his own decisions, but they continue to defer to him for medical and disposition decisions stating, “whatever he wants to do.”

In theory, psychiatrists possess no special skills for determining capacity of a patient to accept or refuse medical care, yet a large percentage of a psychosomatic physician’s work nonetheless involves capacity evaluations.

The goal of the survey was to go beyond ethical lessons, useful as these may be, and to learn how Psychiatric Times’ readers-who are on the front line of psychiatric practice-handle a series of hypothetical ethical scenarios.

As experts in neurobiology, we can conduct and critically evaluate research to identify the short- and long-term risks and benefits of neuroenhancers for patients without recognized clinical indications.

With the availability of drugs for ADHD and Alzheimer disease, more and more healthy people who have no mental health condition have been asking their psychiatrist to prescribe neuroenhancing medications in the hopes of improving their memory, cognitive focus, or attention span. What's an appropriate response when one of your patients asks for a prescription for a drug for this off-label purpose?

This essay does not proffer a change in the classification of specific conditions but will sketch a new meta-concept of evaluative disorders that encompasses a number of prevalent and serious psychiatric diagnoses.

Some psychiatrists include “testimonials” from their patients on their web sites. Such recommendations are a major source of new referrals. . .but is this an ethical way of promoting my clinical services?

Bioethicists often debate whether the rapid pace of medical science truly generates new ethical questions or whether what appear to be novel dilemmas are really ancient conflicts presented in modern terms and contexts.1 The valuable essays in this Special Report offer support for each position and, more important, provide clinical wisdom for mental health professionals struggling with ethical issues both profound and prosaic in a variety of practice settings.

Like millions of Americans, I’ve joined Facebook. I really enjoy it because it conveniently lets me stay in touch with my friends. I don’t tell my patients that I have a Facebook profile, but many patients tell me about their Facebook activities during therapy. How should I respond if a patient to “friend” me?

I’m one of the only psychiatrists practicing in this area. What am I realistically supposed to do when I see one of my patients in public? Whenever I go to the gym or library or grocery store, I see several patients I’m actively treating. Some want to say hello and some want to socialize. My response so far has been to try to avoid them.

The ancient role of conscience as a moral pilot is rejuvenated, and its neglected function as a spiritual daemon is refurbished for more psychologically minded modern readers.

A number of scholars have criticized contemporary bioethics for its focus on what have been called the “neon issues”-end-of-life care, genetic technology, and resource allocation-rather than on the far less dramatic but much more common dilemmas of everyday practice, such as obtaining adequate informed consent for treatment, respecting confidentiality and privacy, and maintaining sound but reasonable boundaries in the therapeutic relationship.1-3 From the “searching and fearless” fourth step of Alcoholics Anonymous to the rigorous spiritual exercises of the Jesuits, many spiritual traditions have proposed a regular and deliberate period of introspection as an effective means of increasing the understanding of and responsiveness to ethical conscience and conduct.

Information transmission, such as blogs, RSS feeds, and podcasts, have emerged as common forms of communication. The exponential growth of medical knowledge and the increasingly rapid pace of scientific discovery have made it nearly impossible for the print medium to keep abreast of new developments.

A 43-year-old woman presented to the ED at 5:30 am on a weekday. While being triaged, she indicated she was hesitant to speak with anyone. The patient reported to the consulting psychologist that she had been deployed to Iraq as reservist nurse 2 years earlier. During that time, an unknown assailant whom she believed to be an Iraqi national working with military security forces sexually assaulted her. The veteran confided that she had been too embarrassed and ashamed to report the assault.

A 24-year-old veteran of Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) presents to the ED mid-morning on a weekday. While the veteran is waiting to be triaged, other patients alert staff that he appears to be talking to himself and pacing around the waiting room. A nurse tries to escort the veteran to an ED examination room. Multiple attempts by the ED staff and hospital police-several of whom are themselves OIF veterans-are unsuccessful in calming the patient or persuading him to enter a room.

A 29-year-old veteran came to the ED complaining of headaches and uncontrolled pain in his upper quadrant. He had been discharged from the military after he sustained a blast injury during duty as a Marine in Iraq. His right arm had been amputated.

Since the time of Homer, warriors have returned from battle with wounds both physical and psychological, and healers from priests to physicians have tried to relieve the pain of injured bodies and tormented minds.1 The soldier’s heartache of the American Civil War and the shell shock of World War I both describe the human toll of combat that since Vietnam has been clinically recognized as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).2 The veterans of Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) and of Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) share with their brothers and sisters in arms the high cost of war. As of August 2009, there have been 4333 confirmed deaths of US service men and women and 31,156 wounded in Iraq. As of this writing, 796 US soldiers have died in the fighting in Afghanistan.3

Eastern philosophy and religion have always had what the philosopher Hajime Nakamura2 called “a preference for the negative.” This stands in stark contrast to our Western penchant for the positive, and our proclivity for defining and intervening is most pronounced in the overactivist mode of modern American medicine."

Recently, I was involved in a discussion with several other mental health writers and editors regarding the most appropriate term to use for those we treat: patient or client. Our lack of consensus reflected that in contemporary medical and psychiatric literature.

Aristotle's concept of the incontinent will and Augustine's concept of the captive will.

"Jack" has been in our emergency department at least 100 times in the 4 years I have worked at the Veterans Affairs Hospital. I first encountered him in the medical ICU, where he was hospitalized multiple times with chest pain and ECG changes after cocaine binges.

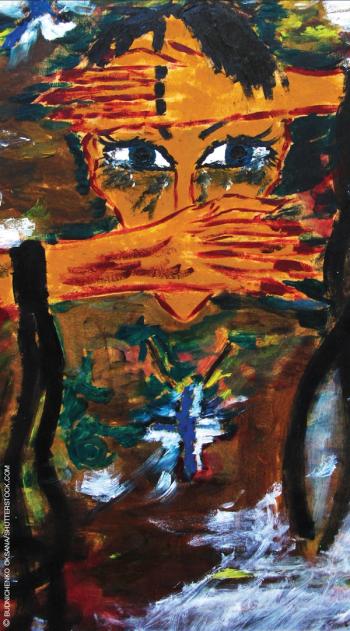

Psychiatrists more than any other medical specialists would benefit from regular doses of poetry, art, and fiction.

It is my great honor and pleasure as a psychiatric educator to teach many excellent medical students and residents. These young and not-so-young men and women are by and large diligent, highly professional, and caring.

In my last column I used the ancient metaphor from Homer's Odyssey of being caught between the two monsters of Scylla and Charybdis to describe the predicament of contemporary physicians treating chronic pain.