- Psychiatric Times Vol 26 No 3

- Volume 26

- Issue 3

DSM-V Transparency: Fact or Rhetoric?

In their response to the commentary by Drs Lisa Cosgrove and Harold Bursztajn in the January 2009 issue of Psychiatric Times (“Toward Credible Conflict of Interest Policies in Clinical Psychiatry,” page 40), David Kupfer and Darrel Regier, the chair and vice-chair, respectively, of the DSM-V Task Force, invite readers to “monitor the most inclusive and transparent developmental process in the 60-year history of DSM at our www.dsm5.org Web site.”

In their response to the commentary by Drs Lisa Cosgrove and Harold Bursztajn in the January 2009 issue of

Psychiatric Times

(

“Toward Credible Conflict of Interest Policies in Clinical Psychiatry,”

page 40), David Kupfer and Darrel Regier, the chair and vice-chair, respectively, of the

DSM-V

Task Force, invite readers to “monitor the most inclusive and transparent developmental process in the 60-year history of

DSM

at our

www.dsm5.org

Web site.” As will be demonstrated in this commentary, this remarkable claim about DSM-V inclusiveness and transparency is simply not true.

First, it should be pointed out that (as noted in the beginning of “

With regard to the truth of the statement that the DSM-V Task Force uses the most inclusive and transparent process in the history of the DSM, the facts speak for themselves.

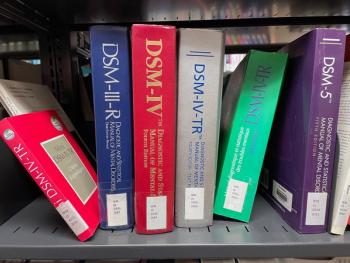

Absence of any information setting forth the principles, goals, criteria for change, etc, underlying the DSM-V revision. Although the Task Force has met at least 7 times in 21/2 years, no information has been provided about such DSM-V fundamentals as the principles guiding the revision process, criteria for making changes, plans to address criticisms of the DSM-IV definition of mental disorder, considerations regarding the future of the multiaxial system, the methodology guiding the empirical review process (including proposed design of the field trials), etc. This is in marked contrast to the DSM-IV revision process, which commenced with the publication of 4 peer-reviewed papers published in the major psychiatry1,2 and psychology journals.3,4 Those articles were written to help educate the field and the public about the development plans for the DSM-IV.

For example, the first paper, which appeared in the Archives of General Psychiatry in 1989-5 years before the publication of DSM-IV1-included detailed sections covering the following topics: advisors to the process, methods conferences, criteria for change, review of evidence, and the development of a source book. The only published materials available at the start of the DSM-V process-namely the DSM-V research agenda5 and the monographs summarizing the DSM-V research planning conferences6-provide absolutely no information about the plans for the DSM-V process itself.

The imposition of an unprecedented confidentiality agreement. DSM-V participants have been required to sign a confidentiality agreement that prohibits them from divulging any confidential information about the DSM-V revision process. That process is broadly defined as “all work product, unpublished manuscripts and drafts and other prepublication materials, group discussions, internal correspondence, information about the development process and any other written or unwritten information in any form that emanates from or relates to my work with the APA Task Force or Workgroup.” Remarkably, that agreement extends beyond the time of the publication of DSM-V. Even with the exception that allows the participant to discuss DSM matters if “necessary to fulfill the obligations” of his or her appointment, this agreement forces the participant into the awkward position of having to decide whether providing information about the DSM is part of his job. In those likely frequent situations in which providing information is not deemed part of the job, this hardly results in a transparent DSM-V.

In contrast, participants of earlier editions of the DSM were never asked to sign any confidentiality agreement nor were they instructed to hold back from discussing DSM matters with anyone.

Restrictions on the appointment of advisors and consultants. DSM-III, DSM-III-R, and DSM-IV were truly inclusive regarding the appointment of advisors and consultants. To get the widest possible opportunity for input, essentially anyone interested in becoming an advisor was appointed.1 While the policy for appointing DSM-V advisors and consultants has never made been public, it is my understanding that the DSM-V Workgroups have been instructed to submit lists of names of advisors for approval by the DSM leadership-and that many proposed advisor appointments have been turned down. Furthermore, in contrast with earlier DSMs in which consultants were appointed for the duration of the DSM revision process, DSM-V consultants are appointed for 1 year only and expressly for the purpose of consulting on a specific issue or problem. Regardless of whether this change in policy makes sense, it is certainly not an example of DSM-V inclusivity.

Although the motivation for this resistance to make DSM-V more transparent remains a matter of speculation, one clear consequence is that it prevents open debate about the directions that the DSM-V Task Force is taking.

It has been extremely challenging to compose any articles raising any concerns about DSM-V because, short of a single article published in CNS Spectrums7 in which Darrel Regier is interviewed by Norman Sussman about DSM-V, there is nothing in print describing the principles underlying the DSM-V revision. What is known to me comes from off-hand comments by DSM-V participants, from grand rounds and other presentations about DSM-V, or from statements to the media.

For example, I understand that in grand rounds presentations given by Darrel Regier, he reports that the thresholds for making changes in DSM-V will be much lower than they were for DSM-IV and that DSM-V will be more etiologically based than DSM-IV. What is the justification for having a lower threshold for making changes? Is there any evidence that the conservative DSM-IV approach was problematic and that important innovations were impeded in some way?

Regarding DSM-V being more etiological, virtually everything that has come out of the DSM-V research agenda and research planning conferences indicates that there is insufficient empirical evidence to justify making the more etiologically based. What is the basis for this astounding claim? Finally, David Kupfer was quoted in a December 27, 2008, article in the Chicago Tribune, saying that his goal for DSM-V was to reduce the number of diagnoses. The deletion of any diagnosis can have profound implications for researchers, clinicians, and patients-to which diagnoses is he referring and what would be the grounds for deleting them?

The wisdom of such potentially major changes in direction need to be discussed and debated out in the open early in the process, well before drafts of criteria are made available in 2010, so that interested parties can respond and provide potentially important feedback. It is only through such an open revision process that the best and most credible DSM-V can emerge.

References:

1. Frances AJ, Widiger TA, Pincus HA. The development of DSM-IV. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:373-375.

2. Frances A, Pincus HA, Widiger TA, et al. DSM-IV: work in progress. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:1439-1448.

Articles in this issue

almost 17 years ago

Brief Psychotherapies: Potent Approaches to Treatmentalmost 17 years ago

Traumatic Stress in Children and AdolescentsEight Steps to Treatmentalmost 17 years ago

Cognitive Difficulties Associated With Mental Disordersalmost 17 years ago

Fishing for Genetic Links in Autismalmost 17 years ago

The New Historical Trauma Studiesalmost 17 years ago

CMS Announces No Changes for Antidepressant and Antipsychotic Accessalmost 17 years ago

Good Clinical Care Requires Understanding Statisticsalmost 17 years ago

FDA Considers Pediatric Indications for AntipsychoticsNewsletter

Receive trusted psychiatric news, expert analysis, and clinical insights — subscribe today to support your practice and your patients.