Challenging the "Dis-ease" Model

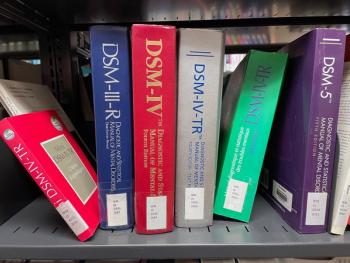

>I greatly enjoyed Dr Ron Pies’ editorial “What Should Count as a Mental Disorder in DSM-V?”1 in which he encouraged framers of DSM-V to critically examine the boundaries of mental illness and to more carefully distinguish between diseases, disorders, and syndromes. As I have noted elsewhere, current plans to integrate a “spectrum” approach into DSM-V require a careful consideration of these issues that must be defensible to critics of diagnostic expansion within psychiatry.2

I greatly enjoyed Dr Ron Pies’ editorial

Echoing DSM-IV’s requirement of “distress and impairment” for most of its disorders, Dr Pies begins with “suffering and incapacity” as core fibers to craft a model of mental disease. He then proposes that progressive discoveries about pathophysiology elevate a syndrome in step-wise fashion toward a disease entity. While this model seems logical enough, I would like to review several challenges that arise from any model that is based on a foundation of “dis-ease.”

The first is the Szaszian issue of society’s role in defining (or creating) suffering and impairment in the context of behavioral disorders. Dr Pies specifically emphasizes the importance of phenomenology-the subjective experience of distress-and also requires that suffering be inherent to the disorder rather than imposed by society (eg, as punishment for deviance). But thinking Socratically, what about conditions in which subjective dis-ease is absent? And what of conditions in which incapacity is defined only by impaired social functioning? Isn’t it sometimes true that a patient with schizophrenia with no insight and no complaints about his or her homelessness, unemployment, and “symptoms” is hospitalized involuntarily because of society’s paternalistic, if not punitive, view of impairment? If that example seems to have obvious holes, what of the thorny history of DSM and homosexuality-if presently excluded based on lack of intrinsic suffering,3 should that same status now be extended to paraphilias (for example, pedophilia)?4

Dr Pies notes that value judgments are unavoidable in diagnosis and notions of disorder and argues that this does not detract from “facts.” In his model, the “facts” seem to be manifest symptoms or known pathophysiologies. Does this mean that any condition with a known physiology that is associated with value-laden suffering or incapacity qualifies as a disease entity? Should human variations that result in less than ideal social functioning and that are almost assuredly rooted in “biomolecular etiology” (eg, ugliness, shortness, baldness, shyness, diminutive sex organs) be categorized as disorders or diseases?5 Part of this dilemma can be sidestepped by arguing that “pathological” suffering should be defined by some threshold of severity, such that therapeutic and cosmetic interventions can be disentangled. But anyone who has ever used a visual analog scale to measure a patient’s self-reported pain can appreciate the difficulties arising from such subjectivity.

Finally, it would appear that disease models that start with “dis-ease” are based on the assumption that “normal” existence does not or should not involve “prolonged suffering or incapacity.” In contrast, Freud wrote of the “common unhappiness” inherent to the human condition-a view now mirrored by proponents of acceptance and commitment therapy,6 Horwitz and Wakefield’s critique of depression,7 or those lamenting “disease mongering.”5,8 Here the underlying issue is causation: is prolonged suffering and incapacity caused by intrinsic pathophysiology, or is subjective dis-ease a “normal” response to extrinsic circumstances (eg, poverty, war, oppression, a less than ideal childhood development)? Such etiological distinctions were deliberately abandoned in DSM-III but seem to be vitally important to the task of defining disease.

These issues are hardly novel and on the contrary have confronted each wave of DSM architects. One can only hope the changes occurring in DSM-V will represent a step forward in accounting for these challenges.

Joseph M. Pierre, MD

Associate Director of Residency Education

UCLA Semel Institute for Neuroscience

West Los Angeles VA Medical Center

Co-Chief, Schizophrenia Treatment Unit

West Los Angeles VA Medical Center

Associate Clinical Professor

Department of Psychiatry & Biobehavioral Sciences

David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA

References

1. Pies R. What should count as a mental disorder in DSM-V? Psychiatric Times. 2009;26(4):17-24.

2. Pierre J. Deconstructing schizophrenia for DSM-V: challenges for clinical and research agendas. Clin Schizophr Related Psychoses. 2008;2:166-174.

3. Spitzer RL. The diagnostic status of homosexuality in DSM-III: a reformulation of the issues. Am J Psychiatry. 1981;138:210-215.

4. Silverstein C. The implications of removing homosexuality from the DSM as a mental disorder. Arch Sex Behav. 2009;38:161-163.

5. Moynihan R, Heath I, Henry D. Selling sickness: the pharmaceutical industry and disease mongering. BMJ. 2002;324:886-891.

6. Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: An Experiential Approach to Behavior Change. New York: Guilford Press; 1999.

7. Horwitz AV, Wakefield JC. The Loss of Sadness: How Psychiatry Transformed Normal Sorrow Into Depressive Disorder. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2007.

8. Smith R. In search of “non-disease.” BMJ. 2002; 324:883-885.

Click "Next" To Read Dr Pies' Response

Dr Pies responds:

I appreciate Dr Pierre’s thoughtful comments on my editorial, as well as his very useful article.1 Among many other issues, Dr Pierre raises the question of what he calls “the Szaszian issue of society’s role in defining (or creating) suffering and impairment.” It is nearly impossible, in this space, to provide a critique of Dr Szasz’s views-which I and others have criticized at length.2-4 Instead, I will try to answer the specific questions raised by Dr Pierre.

First, though, some foundational assumptions: I believe we need to distinguish carefully between the recognition of disease, and the classification of specific diseases. The latter is the subject of Dr Pierre’s excellent article, in which he examines various methods by which psychiatric diagnoses may be “categorized” (eg, based on underlying pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, or both).1

My contention is that these issues ought to follow the recognition of disease, which, in my view, is an everyday determination made on the basis of intrinsic suffering and incapacity of a certain kind. The classification or categorization of such conditions comes later-and constitutes the “upper stages” of the pyramidal model depicted in my editorial. As to the role of causation and etiology: I believe these are unquestionably important in determining the kind of disease that afflicts the patient, but not in determining that the patient has disease, or is “dis-eased.”5

Let me be clear: my model does not regard all instances of prolonged suffering and incapacity as instantiations of disease. A person may experience prolonged suffering and incapacity as a consequence of poverty, physical abuse, or terrorism and would not be considered “diseased” in the sense I wish to define, or in our ordinary usage of the term. Thus, disease entails prolonged and substantial intrinsic suffering, as well as incapacity, in the absence of an obvious exogenous factor that maintains the condition.2

My second assumption is that the construct of disease needs to be “uncoupled” from the issues of its treatment and disposition. That is, the primordial construct of disease is independent of whether we happen to have useful therapies for the patient or whether we decide to hospitalize the patient, either voluntarily or involuntarily. Thus, the thorny legal and ethical issues surrounding involuntary hospitalization are logically distinct from the concept of what counts as psychiatric disease. That said, I believe that involuntary psychiatric hospitalization is justified only when the individual is clearly a danger to self or others; or is so markedly unable to care for himself that he is in danger of death or severe bodily injury.

Finally, my model does not assume that only diseased persons warrant medical care and attention. After all, reconstructive surgeons routinely perform “reduction mammoplasty” without claiming that having large, pendulous breasts constitutes a “disease.” Similarly, there are many emotionally disturbed or dissatisfied individuals who are, in some sense, “suffering” but not incapacitated, or incapacitated but not suffering, and who may nevertheless benefit from psychiatric interventions-yet they would not be called “diseased” using my schema.

On the other hand, the legal system sometimes places psychiatrists in the uncomfortable position of having to provide involuntary “treatment” to individuals-such as serial sexual predators-who are neither suffering nor incapacitated, but who are deemed a threat to society. These persons may in some sense be “disordered,” but I would not regard them as “diseased.” Under certain legal doctrines, society may have a right to keep them confined, but it is far from clear that they will benefit from psychiatric hospitalization.

With this background in mind, my responses to Dr Pierre’s questions are as follows:

1. Conditions in which subjective “dis-ease” is usually absent and that typically lack “intrinsic suffering”-for example, ego-syntonic pedophilia-should not be considered instantiations of disease, although they may require societal intervention or control.

2. Regarding patients with schizophrenia but who have “no complaints about . . . homelessness, unemployment, and [their] ‘symptoms’ . . . ”: such individuals are extremely rare, in my clinical experience. While it is true, as Dr Pierre notes, that “delusions and hallucinations may or may not be subjectively distressing,”1 it would be exceedingly rare for someone with chronic schizophrenia to have experienced no intrinsic suffering as a result of this condition. Such suffering may not be a direct consequence of hallucinations or delusions but may stem from severe dysregulation of volition, motivation, mood, and “ego integration.”6 These phenomena are not merely examples of “social” impairment, nor are they merely the result of society’s disapproval or “labeling.” Rather, they are intrinsic experiential dimensions of the person’s psychosis. Moreover, as Dr Pierre1 himself points out, many individuals with schizophrenia experience neurocognitive difficulties that limit their ability to process and analyze information, resulting in both incapacity and subjective distress.

3. With respect to what Dr Pierre calls “human variations that result in less than ideal social functioning” and that have “a known physiology,” such as shortness or baldness: such normal variants would not constitute disease, using my model, because they are not typically associated with intrinsic suffering and substantial incapacity (although they may be the objects of derision or discrimination).

4. My model of disease does not rest on the assumption that “normal” existence does not, or “should not,” involve prolonged suffering or incapacity. However, I do assume that physicians have an ethical and humanitarian interest in reducing disease-based suffering and incapacity.

In closing, I would emphasize that there is no “correct,” objectively verifiable definition of psychiatric disease or mental illness that we have yet to “discover”-as if we were hunting for some buried treasure that has mysteriously eluded us. Nor is there ever likely to be a universally useful definition of “disease” that covers all legitimate cases and excludes all spurious ones. I believe Dr Pierre appreciates this when he writes that “medical diagnosis serves different functions” ranging from communication to treatment to definition of pathophysiology.1

Indeed, in my view, what we call “disease” or “disorder” is radically dependent on specific human needs, goals, and purposes. A definition of disease that may serve the purposes of an infectious disease expert may not serve those of an internist or psychiatrist. To borrow from Ludwig Wittgenstein: we may ultimately be left with a “family” of conditions we call disease, which lack any necessary and sufficient defining features, but which cohere in so far as they entail severe and prolonged suffering and incapacity.

Ronald Pies, MD

Professor of Psychiatry

SUNY Upstate Medical University

Syracuse

Clinical Professor of Psychiatry

Tufts University School of Medicine

Boston

Editor in Chief, Psychiatric Times

References:

References

1. Pierre J. Deconstructing schizophrenia for

DSM-V

: challenges for clinical and research agendas.

Clin Schizophr Related Psychoses.

2008;2:166-174.

2. Pies R. On myths and countermyths: more on Szaszian fallacies.

Arch Gen Psychiatry

. 1979;36:139-144.

3. Pies R. Moving beyond the “myth” of mental illness. In: Schaler JA, ed.

Szasz Under Fire

. Chicago: Open Court; 2004:327-353.

4. Kendell RE. The myth of mental illness. In: Schaler JA, ed.

Szasz Under Fire

. Chicago: Open Court; 2004:29-48.

5. Pies R. Depression or “proper sorrows”-have physicians medicalized sadness?

Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry

. 2009;11:38-39.

6. McNeil EB.

The Psychoses

. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1970.

Newsletter

Receive trusted psychiatric news, expert analysis, and clinical insights — subscribe today to support your practice and your patients.