Six fundamental assumptions underlie the medical model most psychiatrists use in their clinical work.

Dr Pies is Professor Emeritus of Psychiatry and Lecturer on Bioethics and Humanities, SUNY Upstate Medical University; Clinical Professor of Psychiatry, Tufts University School of Medicine; and Editor in Chief Emeritus of Psychiatric Times (2007-2010). Dr Pies is the author of several books, including several textbooks on psychopharmacology. A collection of his works can be found on Amazon.

Six fundamental assumptions underlie the medical model most psychiatrists use in their clinical work.

There are no simple solutions to the plight of the terminally ill patient. With commentary by Cynthia Geppert, MD.

The nightmarish reality of psychosis is vividly detailed by Deborah Danner, a woman with self-described schizophrenia, recently shot to death by a New York City policeman.

The supposed “epidemic” of mental illness turns out to be mostly a myth in the US adult population, 2000-2015.

The ethical core of the Goldwater Rule is sound, but the rule needs clearer and more nuanced language.

The authors examine the literature on "quality of life" and how antipsychotics improve that for patients with schizophrenia.

Should doctors be legally allowed to assist terminally ill patients in committing suicide?

For patients suffering the chronic, debilitating symptoms of schizophrenia, antipsychotic medication is a critical component of treatment-and may literally be life-saving.

How radically do we want to alter the physician’s traditional ethical obligations to the most vulnerable of patients?

Both the literature and clinical experience point to considerable risk in discontinuing antipsychotic treatment, for many chronically psychotic patients. Here's why.

We can teach patients a lot about the biopsychosocial causes of depression-even in 5 minutes.

What can we do, as a society, to reduce the levels of incivility and narcissism that appear to be on the rise?

Gun violence by alienated, disgruntled individuals isn't new. So what changes may help account for our recent spate of mass shootings?

Most psychiatrists do not fit neatly into the biological or psychodynamic camps. Instead, like surgeons, they will implement tools that reduce the suffering and enhance the well-being of the patient.

If serotonin was once American psychiatry’s “high school crush,” the field now appears wedded to a more mature model of biological and psychosocial understanding.

Ronald Pies, MD reviews the second edition of Ansari and Osser’s overview of psychopharmacology.

May we forgive a murderer on behalf of his victims?

Critics of psychiatry claim there is an “epidemic” of mental illness in the US-and some argue this is a consequence of psychiatric treatment. But the best epidemiological evidence reveals no such epidemic in this country, rendering the iatrogenic “explanation” null and void.

There is a myth circulating in the blogosphere-usually among the most extreme critics of our profession-that there exists some monolithic entity called “Psychiatry” (with a capital “P”).

For many of us who went into psychiatry, relieving the patient’s suffering is not a business enterprise, but an ethical and spiritual calling.

A recent report that argues against descriptive diagnosis in medicine is historically ill-informed and medically naive, in the opinion of this psychiatrist.

What do physicians intend by the term “disease”? The recent IOM report on “systemic exertion intolerance disease” (formerly known as chronic fatigue syndrome) casts this question in a new light and has many practical implications for patients, physicians, and third-party payers.

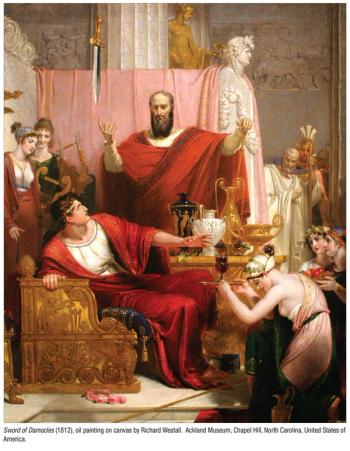

Readers of Albert Rothenberg’s new book will come away greatly enriched by the author’s own lifelong, creative synthesis.

A commentary on civility and ethical standards in the aftermath of terrorist events in France.

“Distress” hardly captures the inner world of those with severe forms of psychotic illnesses. Terms like “agony,” “torment,” and “anguish” would be much closer to the mark, for many patients.

There are probably many social, economic, and familial forces at work in generating the trend toward public incivility, and it would be silly to blame the Internet for the riot in Keene.

The “story behind the story” is not the over-prescription of antidepressants-though it happens-but the under-availability of optimal treatment.

If you’ve never surfed the web for sites that critically examine psychiatry, I highly recommend it-though it’s not for the faint of heart.

A limited sampling presented here lends no support to Dr Thomas Szasz’s claim that 19th century physicians regarded the term “mental disease” as merely a figure of speech; on the contrary, several prominent physicians of this era recognized such conditions as both real and debilitating.

It is time for psychiatry’s critics to drop the conspiratorial narrative of the “chemical imbalance” and acknowledge psychiatry’s efforts at integrating biological and psychosocial insights.