Throughout this troubled year, we have learned much that will allow us to make the world a better place.

Throughout this troubled year, we have learned much that will allow us to make the world a better place.

How can psychotherapy become a mature science?

Are patients with depression and substance use disorder getting an appropriate level of care? Our Journal Club piece investigates.

According to a recent study, certain product combinations of alcohol and cannabis may be less likely to cause negative consequences.

The authors make the case for national education mandates from accreditation organizations and congressional support to require enhanced education of all clinicians who care for older adults.

As the pandemic and social issues rage on, a palpable and consistent theme runs through us, and that is the very best of human behaviors.

Mutations in PCM1, a gene crucial to neuronal cilia function, have been connected with schizophrenia, according to a recent study.

On the etymology of the "Feinerism."

The PHQ-9 may be an effective asset in a clinician’s toolkit, along with their clinical judgment and therapeutic alliance, to ensure treatment planning and outcome tracking is personal to each patient.

The Lumipulse® G β-Amyloid Ratio in vitro diagnostic test was filed for 510(k) premarket clearance.

This book provides key tools to help combat racism in the mental health profession.

An insider’s look at how balancing COVID-19 safety protocols and affording teens a safe space to interact and bond has made this challenging year less daunting.

A new study associates a gene that facilitates neuron communication in the nervous system with memory loss.

A drug developed to treat high blood pressure has unexpected benefits for patients with severe withdrawal symptoms.

Female emergency department patients with adverse childhood experiences were more likely to have substance use issues.

A new study finds that isolation makes us want company on a neural level, in much the same way that hunger makes us want food.

Sexual minorities with alcohol and tobacco addictions are at a higher risk for comorbid psychiatric disorders, bisexual women in particular.

An immunosuppressed clinician realizes that limits does not mean that you are limited.

Throughout history and across cultures, monsters have helped communities teach lessons and affirm their values.

Suicide attempts among pregnant or postpartum mothers have nearly tripled over the past decade.

D-cycloserine may help patients with anxiety disorders, or it might make their anxiety worse. Find out how to use it safely.

Drug use is not only a consequence of addiction. It can also be a response to a deeper, existential problem.

A mother begs the court to keep her son incarcerated for fear street gangs will eat him alive.

How has the COVID-19 pandemic affected the way young adults use substances like vaping, alcohol, and marijuana?

The COVID-19 pandemic has been a moment of truth for telehealth, and, by most accounts, the technology is rising to the challenge.

Key leaders experienced in real-world clinical practice share on a range of topics.

The high co-occurrence of chronic pain and PTSD and their possible entanglement underline the importance of conducting assessment for both conditions.

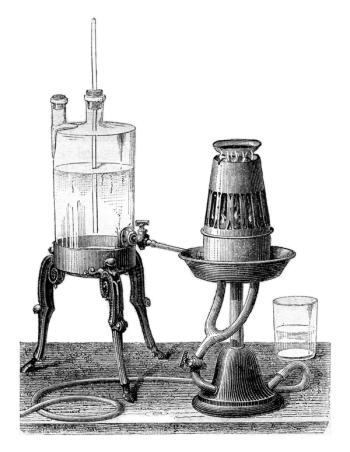

A prominent forensic psychiatrist and the grandson of founding father Alexander Hamilton, Allan McLane Hamilton, MD, was a proponent for the use of nitrous oxide for diagnostic and therapeutic use.

Pain may not often be considered within the realm of psychiatry; however, chronic pain's relationships with sleep disorders and PTSD make it an issue psychiatrists can—and should—address.

Sleep disturbance and chronic pain work together to cause misery for patients, with one exacerbating the other. Here: Tips to address both and bring peace to patients.