Keys to diagnosis, assessment, and management.

Keys to diagnosis, assessment, and management.

I offer all of this as a way of describing how I became involved in intensive psychotherapeutic efforts with several adolescents who I then continued to see, often for many years following their inpatient experiences.

When I was an undergraduate studying molecular biology in the early 1990s when the Human Genome Project had just begun, my required coursework included several lectures on the ethical implications of sequencing, understanding, and ultimately being able to manipulate the “code of life.”

Consider the predicament of Mrs M-a 38-year old premenopausal mother of two. Mrs M tells her primary care physician, “I just don’t have a strong desire for sex."

The risk of breast cancer recurrence related to some SSRI antidepressants interacting with and reducing the effectiveness of tamoxifen was quantified in 2 epidemiological studies published in February.

How regularly do you use outcome measures to assess how well your patients with depression are doing? Research suggests many psychiatrists avoid such measures, believing that they are aren’t trained to use them; that they take too much time; or that they aren’t clinically helpful.1

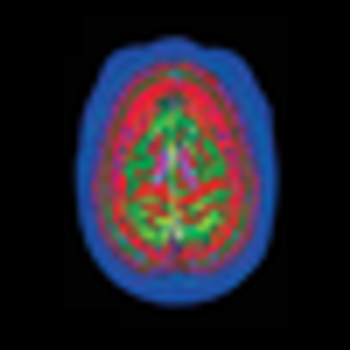

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is noninvasive focused brain stimulation that uses pulsed magnetic fields. The underlying mechanism depends on the principle of electromagnetic induction, the process (discovered by Faraday in 1839) by which electrical energy is converted into a magnetic field and vice versa.1

The recently posted draft of DSM5 makes a seemingly small suggestion that would profoundly affect how grief is handled by psychiatry.

This is the second installment of a new series in which clinically relevant research is briefly discussed and, perhaps more important, a few tips on how to read and interpret research studies are presented. Your feedback, suggestions, and questions are eagerly solicited at rajnish.mago@jefferson.edu.

The overall effectiveness of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is well known, but its speed of action is much less talked about. Here I review what is known about the time course of action of ECT in depression.

Houston, we have a problem. There is a critical shortage of psychiatrists.

In 5 minutes, so much can be accomplished.

Sometimes you spot a serious problem and figure out a very well-intended solution, only to discover eventually that your solution created as much trouble as the original problem. The workers on DSM5 have spotted an enormously worrying problem-the wild overdiagnosis of childhood bipolar disorder (BD) which has led to a massive increase in the use of antipsychotic and mood stabilizing medications in children and teenagers.

Help in Clinical Decision Making

Mark Twain observed that "the past may not repeat itself, but it sure does rhyme." An unfortunate rhyme in psychiatric history is the recurrence of fad diagnoses. Childhood Bipolar Disorder is the most dangerous current bubble, with a remarkable forty-fold inflation in just one decade.

Avoid Surprises and Unintended Consequences

Available treatments are so robust that nearly one-third of patients with major depression will achieve full clinical remission with monotherapy.

Diagnostic Dilemmas-Effective Treatment Approaches

The recently posted draft of DSM5 makes a seemingly small suggestion that would profoundly impact how grief is handled by psychiatry. It would allow the diagnosis of Major Depression even if the person is grieving immediately after the loss of a loved one. Many people now considered to be experiencing a variation of normal grief would instead get a mental disorder label.

Parkinson disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative illness in the United States, affecting more than 1 million persons. Disease onset is usually after age 50. In persons older than 70 years, the prevalence is 1.5% to 2.5%.1 While the primary pathology involves degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra, circuits important in emotion and cognition-such as the serotonergic, adrenergic, cholinergic, and frontal dopaminergic pathways-are also variably disrupted.

Writer Jonah Lehrer caused quite a stir with his recent article in the New York Times Magazine, with the unfortunate title, “Depression’s Upside.” I have a detailed rejoinder to this misleading article posted on the Psychcentral website.

Arlington, VA, March 2 (compiled from AP reports)-Officials at the American Psychiatric Association (APA) confirmed today that their national headquarters had been taken over by “very, very large English and literature teachers,” according to a spokesperson for APA President, Dr Alan Schatzberg. Schatzberg himself was unavailable for comment and was reported to be in seclusion “…brushing up his Shakespeare.”

Quick-which screening test or instrument has greater specificity for the target condition: the PSA (prostate specific antigen) test for prostate cancer, or the BSDS (Bipolar Spectrum Diagnostic Scale), for bipolar disorders?

Another lifetime ago-just after leaving residency-I took a job as a psychiatric consultant at a large, university mental health center. Had I known the poisoned politics of the place, I would have headed for someplace safe-like, say, Afghanistan.

“The exclusion of symptoms judged better accounted for by Bereavement is removed because evidence does not support separation [or] loss of loved one from other stressors.”1